Writing historical fiction doesn't mean distorting the past, says Dave Martin. So why not encourage children to create their own adventures

I fell in love with history when, aged 11, I won a copy of The Woolpack (Puffin, 1951) by Cynthia Harnett. Her story, a little dated now, took me back to the Cotswolds in 1493. But this was no dull and distant world. Instead it was a vibrant, exciting and immediate place that I saw, heard, smelt and shared through the experiences of a young boy little older than myself. This is how Harnett opens her story:

Nicholas Fetterlock lay on his back on the hillside, gazing up into the young leaves of an oak tree.

He was hot and dirty, and it was good to stretch his full length in the shade. All around him from far and near came the bleating of sheep – the high anxious cry of lambs and the deeper reassuring answer of the ewes. Further away he could hear the voices of the village children. They were wool-gathering, down near the river, collecting every fragment of fleece that the sheep had left caught on hedges and bushes. Presently they would take it home to their mothers who would wash it and spin it and make it into warm garments for the winter.

Immediately we meet the main character and are intrigued. Why is Nicholas hot and dirty? Already we sense we are in a past time when village children gathered wool and their mothers spun it to make their clothes. This, then, is the first reason for using historical fiction in the classroom: its power to engage the reader.

Historical fiction is sometimes criticised for being unwittingly misleading, but a good writer will create a detailed and complex picture of the past without it being distorted. To quote the author Jill Paton Walsh, ‘The writer may invent characters, conversations and circumstances, but if the book is a good one, the invention will all be with the grain of the known historical evidence, and will illuminate’. As a result, discussions about the veracity of historical fiction in itself can also lead to useful learning.

To begin with you need a good book. But simply reading historical fiction is not enough; to extract maximum value from it children also need to write their own. The two activities - reading and writing - perfectly complement each other and, in the process, so do the curriculum requirements of history and English.

If children are to create convincing characters and settings they have a reason to esearch authentic detail. So writing requires research. And children cannot simply write historical fiction; they need to be taught the writer’s techniques. It is this detailed working with texts that is the final reason for using historical fiction. It improves children’s writing.

Now, the features of a good historical story are:

• Engaging characters

• Authentic setting

• An interesting plot involving the characters in solving a problem

• Atmosphere

• Tension/suspense

• Pace

• Surprise

• A sense of period, of being in the past.

Each of these can be taught. To take ‘authentic setting’ as an example, the extract from The Spitting Cobra by Gill Harvey (Bloomsbury, 2009) is illuminating. She was one of the Young Quills Award winners in 2011.

The house of Nakht was packed, and the inner room was hot. Very hot. Lamplight flickered around the walls, creating deep, twisting shadows that leaped and cavorted in time with the music. Nefert, Sheri and Kia were playing their instruments faster and faster, while Paneb beat out the rhythm with a pair of clappers. Mut and Isis gyrated and swayed to the music, their bodies shining with fragrant oil.

The room was crowded with people. Men holding beakers of wine stood cheering and clapping. Women sat along one wall dressed in their finest linen and jewellery – beautiful beaded collars and gold bangles that glinted in the lamplight. Perfume cones sat on top of their wigs, slowly melting, filled the room with rich, sweet scent.

First it should be read aloud. This helps children to listen to the music, the rhythms of the language. With role-play or freeze framing they might then try to recreate this dancing scene, and then perhaps compare it to an Egyptian tomb painting, Nebamun’s perhaps. Then, in talking around the detail of the text, children can be helped to identify the literary techniques Gill Harvey has employed. She uses a variety of sentence styles to add interest from the long descriptive sentences that create atmosphere to the short, ‘Very hot’. Children can be shown how those sentences deliberately cover the senses of sight, sound and smell. And within them children can spot the skilful word use - the dancers ‘gyrated’, the lamplight ‘flickered’ - and the apt use of alliteration; the men ‘cheering and clapping’, the women wearing ‘beautiful beaded collars’. Children can also be alerted to the use of repetition, the ‘inner room was hot. Very hot.’; the musicians who played ‘faster and faster’.

All of this is underpinned by accurate historical detail, not detail simply included to inform the reader in a dull and worthy fashion, but rather detail that creates a vivid setting and atmosphere.

Classroom experience has shown that once children are aware of such techniques - when they have begun to think critically about the texts they read - then they are able to borrow and use those techniques in their own writing. So an historical enquiry can be built around children reading a text, or extracts from that text, set in a particular period. When they are comfortable in that period they can then write their own historical fiction, drawing upon the author’s techniques. Thereafter the writing and researching go hand in glove.

Visit Dave Martin’s blog (davemartin46.wordpress.com) for more information on children’s historical fiction that includes extracts and suggestions for classroom use.

Once children begin to enjoy exploring the past through fiction, why not enter their stories for the history association’s historical fiction prize?

This short extract, taken from a previous entry, has been written by a confident writer who has used dialogue to open his story:

‘Lucius, go, now, quickly!’

His father’s shouts echoed through the villa.

‘It’s them Lucius, it’s the legionaries, run!

The crashing at the door was getting more and more violent.

There was a splintering sound as half of its wooden panelling

came away.

‘Hurry!’

It’s a fine example of how pupils can weave together history and fiction. The main character is introduced immediately and the problem that drives the plot is signaled: Lucius is in trouble. nd the subtle use of detail - villa, legionaries and the name Lucius itself – suggests we are in Roman times.

To make it easier for teachers to incorporate the competition into their lessons, pupils can base their stories in any period or place in the past. The judges will be looking for historical fiction with a convincing setting and entry forms can be downloaded from the History Association’s website (history.org.uk).

Author Harriet Castor traces her desire to write historical fiction back to her formative years…

Author Harriet Castor traces her desire to write historical fiction back to her formative years…

I’m obsessed with history. I love it. When I try to work out why, it traces back to the fact that my mum and dad weren’t madly keen on bucket-and-spade holidays. So instead, when I was a kid, we spent our summers visiting old buildings – castles, churches, stately homes, the ruins of monasteries. Their worn stone steps fascinated me; I thought of all those feet walking to and fro. I stood in rooms, looked at views, and thought of the people who had stood in exactly the same spot over hundreds of years. People who laughed and argued, tripped over, got the hiccups and were, in short, every bit as alive and human as me. They seemed so close. Why could I not see them? I was mystified, frustrated. It was as if a thin filmy layer of some strange substance separated me from the past – and if I could only push through it…

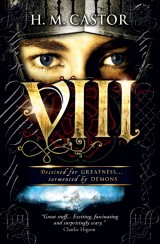

Writing historical fiction is my way of pushing through that filmy layer. ‘Few people think that distance is mysterious,’ says Prof. David Deutsch, a quantum physicist, ‘but everyone knows that time is.’ This is what inspires my writing. The mysterious fact that people like us have been here, done astonishing things, lived and loved and disappeared forever, is endlessly fascinating to me. When writing my book VIII (the story of Henry VIII, told from his own point of view) I wanted the reader to forget the gap between the past and the present. I hope that if your pupils read VIII they’ll think, not ‘eww, how weird the world was then’, but ‘that could have been me.’

Dave Martin was a full time history teacher and local authority adviser for twenty three years before becoming a freelance adviser. He runs the Historical Association’s Write Your Own Historical Story Competition for children.

How to be a singing school

Ace-Music

Boosting children’s self esteem

Ace-Classroom-Support

Easy ways to combat teacher stress

Ace-Heads