Put down that battered text book and try using original WWII documents to inspire your next topic on evacuation, suggests Alf Wilkinson...

Sometimes when you’ve taught a topic several times you become very familiar with the key ideas and subject knowledge. You know which book has the most striking images, which worksheet offers the greatest challenge, or which film clip will best engage your pupils. But sometimes, going back to original documents can make you and your pupils see a topic in a different light. Take, for instance, the topic of evacuation.

We usually teach that, once war was about to start, evacuation swung into action, removing all the children from cities in danger of eing bombed. Over 1.4 million people were evacuated in Britain in the first few days of the war. They were evacuated by train, taken to areas considered safe from German bombs, and left in resettlement centres where local people turned up and selected the evacuees they wanted. And there they stayed until the end of the war in 1945. We also know from people’s reminiscences that the experience was either a happy one, or very difficult, depending on the place they found themselves and the adults in charge. But is this an accurate picture?

We usually teach that, once war was about to start, evacuation swung into action, removing all the children from cities in danger of eing bombed. Over 1.4 million people were evacuated in Britain in the first few days of the war. They were evacuated by train, taken to areas considered safe from German bombs, and left in resettlement centres where local people turned up and selected the evacuees they wanted. And there they stayed until the end of the war in 1945. We also know from people’s reminiscences that the experience was either a happy one, or very difficult, depending on the place they found themselves and the adults in charge. But is this an accurate picture?

The archives of the Women’s Royal Voluntary Service (wrvs.org.uk) present a slightly different picture. Here is an extract from a report on evacuation to the South West of England.

Main body of evacuee had left by the end of December: out of 780 in September only 139 remained; it suggested that pressure from home and economic difficulties were the cause.

Why, by Christmas 1939, had 641 evacuees gone home from this one small town in Somerset? Already this short extract from a WVS report is beginning to paint a slightly more complicated picture of evacuation.

Why, by Christmas 1939, had 641 evacuees gone home from this one small town in Somerset? Already this short extract from a WVS report is beginning to paint a slightly more complicated picture of evacuation.

What picture emerges if we look at the figures for one Reception Area throughout the war? Here are selected figures for Haslemere, in Surrey, taken from the monthly reports for the town:

What happens to the number of evacuees between September 1939 and June 1940? Does that reflect the experience of Dulverton in Somerset? Does each source back the other up? What happens to the number of evacuees between June 1940 and November 1940? Can you explain why the number of evacuees increases so much in this time? What was happening in the war? What happens to the totals after 1940? Can you explain why the number of evacuees goes down so much? Is there a difference in what happens to the totals for ‘unaccompanied children’ and those for ‘adults and children?’ Can you explain any difference? In some areas there is a second surge in evacuee numbers in 1944, as the V1 and V2 rockets attack South East England, ausing nearly as many deaths as the Blitz of 1940 and 1941, but this does not happen in Haslemere. Can you explain why not?

As well as providing us with the opportunity to analyse and interpret data, original sources can also help us to speculate about what life might have been like for the children once they were evacuated. Were they left on their own to cope with their new situations as best they could? What support did the community offer?

As well as providing us with the opportunity to analyse and interpret data, original sources can also help us to speculate about what life might have been like for the children once they were evacuated. Were they left on their own to cope with their new situations as best they could? What support did the community offer?

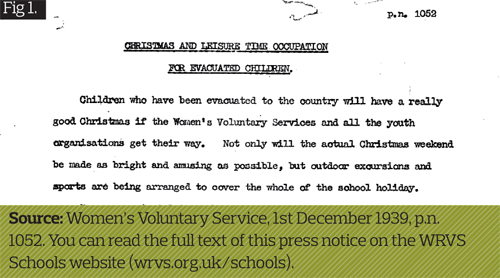

Below is an extract from a document published by the Women’s Voluntary Service in December 1939 (see Fig.1).

Does it sound like Christmas will be fun for these 3,500 evacuated children? What do you think of the proposed activities for the Christmas holiday? Do they sound like things the children would normally do in London over Christmas in the 1930s? Because the WVS announces them in a press release, does that mean they actually happened? How could we find out if they happened or not?

Most of the data used in this article is taken from monthly reports collected by local offices of the WVS; or, in the case of Christmas 1939, a press release. As such, they are useful in providing us with an insight into how one group of people, those at the sharp end organising the nitty gritty detail of evacuation and caring for the evacuees, saw the events of 1939 and after. They are not propaganda posters used to persuade people to evacuate from the cities, which are often used in lessons. They are also not personal reminiscences of being evacuated, which, as oral history, can be very important in helping us to understand what it was like to be an evacuee, but that sometimes present the past through rose-tinted spectacles. They give us another perspective on the process. By using all these sources together, we can build up a more detailed picture of evacuation, warts and all.

Most of the data used in this article is taken from monthly reports collected by local offices of the WVS; or, in the case of Christmas 1939, a press release. As such, they are useful in providing us with an insight into how one group of people, those at the sharp end organising the nitty gritty detail of evacuation and caring for the evacuees, saw the events of 1939 and after. They are not propaganda posters used to persuade people to evacuate from the cities, which are often used in lessons. They are also not personal reminiscences of being evacuated, which, as oral history, can be very important in helping us to understand what it was like to be an evacuee, but that sometimes present the past through rose-tinted spectacles. They give us another perspective on the process. By using all these sources together, we can build up a more detailed picture of evacuation, warts and all.

Children love using original sources like this and find them endlessly fascinating. Using original sources also helps to remind us that history is very complicated. For example, if children and young mothers were evacuated to Dulverton they would have had a different experience than if they’d been sent to Haslemere. It also reminds us that the official policy, that evacuation happened smoothly in September 1939, is not the whole picture and that thousands of unknown and unsung volunteers played a huge part in the process.

You can find lots more original sources about the Home Front during WW2 – and activities to go with them for KS2 – on the website, The Army That Hitler Forgot, at wrvs.org.uk/schools.

Alf Wilkinson works for the Historical Association, and has recently worked with the Women’s Royal Voluntary Service archive to produce a website for teachers about life on the Home Front during World War II, wrvs.org.uk

Find original WWII source materials at wrvs.org.uk/schools

Why Boarding School Fiction Feels Comfortably Familiar

Ace-Classroom-Support

Use the bottle-flipping craze to create good school behaviour, not bad

Behaviour Management

The side effects of teaching music

Ace-Music