With a good work of historical fiction, you can tempt children to discover more about the past, says Juliet Desailly...

There is nothing like a work of historical fiction to immerse you in a particular period and build an understanding of how people lived in the past. For many people it has proved the starting point for a life long love of history. Fiction based in the past can be used for teaching all the usual elements of a narrative text whilst providing a rich historical context for the children. It can also stimulate enquiry and research. Historical fiction doesn’t just have to support work in history or literacy, though. It is also the perfect way into learning in a range of different subjects.

There are a few things to consider when choosing a text. First, and most important, is that it has to be a good story in its own right, and age-appropriate. In general, children can cope with texts that would be slightly too difficult for them to read themselves. Reading such books aloud also gives you the opportunity to offer explanations as you go. However, bear in mind that it is important to find the balance between keeping the story flowing and stopping to explain things or discuss issues.

The second most important consideration is that of historical accuracy. Some authors try too hard to make their central characters ‘just like us’ in an attempt to engage and form a connection with the young reader. This can lead to anachronistic activities or views being portrayed that just wouldn’t have happened. The Historical Association (history.org.uk) reviews many children’s historical novels and will let you know how accurate your chosen text is.

A good first and ongoing activity is to ask the children to draw illustrations for particular scenes in the story. If it is the first time they have done this, model the process of reviewing the text to make deductions about the setting, characters, relationships and activities that children will later depict. Have there been details, such as descriptions, elsewhere in the story so far that they need to take into consideration? Children should then list what they need to research such as clothes, hairstyles, landscape, houses, artefacts or modes of transport. When they have done enough research to be clear about their illustration, they can begin drawing. Sharing and discussing each others’ illustrations can provide good insights into elements they may have missed or misinterpreted and will inform their next attempts.

When everyday activities such as meals, getting dressed or journeys are described in the text, ask the children to make a chart showing similarities and differences between how we undertakesimilar activities now and how they were carried out in the period of the story. This can be ongoing, with the children adding to their chart as new things are discovered during the story. It is also useful for children to include a list of questions on what else they would like to find out about the period in their books or on a working wall. The questions can later be shared out amongst groups or individuals and time found for students to research the answers. This can also make a good homework activity.

When everyday activities such as meals, getting dressed or journeys are described in the text, ask the children to make a chart showing similarities and differences between how we undertakesimilar activities now and how they were carried out in the period of the story. This can be ongoing, with the children adding to their chart as new things are discovered during the story. It is also useful for children to include a list of questions on what else they would like to find out about the period in their books or on a working wall. The questions can later be shared out amongst groups or individuals and time found for students to research the answers. This can also make a good homework activity.

As you read the book there are bound to be references to items, practices or deities that the children do not recognise or know to be different from modern equivalents. Suggest to the children that the class compiles a glossary to complement the book. After each chapter or section is read, ask the children to review it and make note of anything they do not recognise or understand or that they think other children might not know. They should find out what these things are and write their own definitions, perhaps with an illustration where suitable. They might even send their completed glossary to the publishers for consideration in subsequent editions, or print it themselves for the next class that reads the book.

If there are illustrations in the book (or if the children have made their own), choose one and provide a copy to pairs of children. Give them a small circle of plain paper about the size of a 2p piece. Ask the children to draw their own face on the circle and then use it to cover the face of a character in the picture. In this way they ‘step into the picture’ themselves. If they don’t want to identify with a particular person in the picture they can place themselves as observers somewhere in the scene. Ask them to imagine what they would hear, see, taste, smell, feel (touch) or feel (emotionally) if they were there. Encourage children to generate really good descriptive phrases or sentences to illustrate these senses. You could also ask the children to produce their own soundscape or background track for a radio version of the scene and record it.

If there are illustrations in the book (or if the children have made their own), choose one and provide a copy to pairs of children. Give them a small circle of plain paper about the size of a 2p piece. Ask the children to draw their own face on the circle and then use it to cover the face of a character in the picture. In this way they ‘step into the picture’ themselves. If they don’t want to identify with a particular person in the picture they can place themselves as observers somewhere in the scene. Ask them to imagine what they would hear, see, taste, smell, feel (touch) or feel (emotionally) if they were there. Encourage children to generate really good descriptive phrases or sentences to illustrate these senses. You could also ask the children to produce their own soundscape or background track for a radio version of the scene and record it.

Charting similarity and difference in physical things, as in activity 2, is relatively easy. There are differences in attitudes, however, which are far more difficult to understand. Take the time to discuss issues that occur or might have occurred. For example; were attitudes to boys and girls, to children working, to education, to magic, to religion or to race different to ours? It might be a good opportunity to cast yourself in the role of a character in the story and allow the children to ask pre-prepared questions about your views and behaviour. Being in role yourself, rather than using a child, means that you can bring out subtleties and complexities about beliefs in the past and can challenge the children to justify their own views.

Investigate ancient egypt through Juliet’s own historical fiction and free workshops…

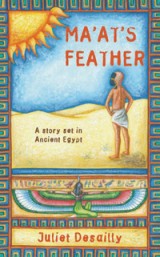

Juliet Desailly is an author and educational consultant. Her children’s novel Ma’at’s Feather, set in ancient Egypt, is designed for KS2 children.

Juliet runs free workshops in schools (expenses payable outside London). She discusses writing the book and the publication process, answers questions and will conduct a workshop making masks of Anubis.

A companion book, Cross-Curricular Lesson Ideas based on Ma’at’s Feather is also available for teachers. The materials provide over 30 creative, cross-curricular lesson ideas based on the story, many of which would fit comfortably into literacy hour and others of which support teaching and learning in the foundation subjects.

Praise For Ma’at’s Feather: ‘Traditional farming life, death, rituals and belief in the afterlife all feature in this beautifully written story. Highly readable and historically accurate.’ – Historical Association ‘A great story. You are drawn in very quickly and presented with a richly described and historically accurateancient world.’ – Teach Primary magazine

Praise For Ma’at’s Feather: ‘Traditional farming life, death, rituals and belief in the afterlife all feature in this beautifully written story. Highly readable and historically accurate.’ – Historical Association ‘A great story. You are drawn in very quickly and presented with a richly described and historically accurateancient world.’ – Teach Primary magazine

For further details visit julietdesailly.co.uk

KS2 Lesson plan: China and Buddism

Ace-English

Make every lesson an experiment

Cross Curricular