If the only tool children have is a hammer, say Simon Percival and Steve Bowkett, they’ll approach every problem as a nail...

‘PeopleWyse’ is the name we have given to the development of emotional resourcefulness in children through the cultivation of life coaching skills. The raft of techniques we explore in our series of articles is underpinned by a definition of creative thinking which incorporates the two key elements of:

• making new connections

• looking at things in a number of ways

Encouraging children to link ideas in increasingly sophisticated ways – i.e. to join up ‘little ideas’ to make more complex ones – turns disparate items of knowledge into information. Being able to look at ideas, experiences, problems etc. in a variety of ways keeps thinking flexible and fresh and dampens the tendency to use so-called ‘routine’ thinking skills. Such a tendency has been summed up in the idea that if the only tool you’ve got is a hammer you’ll treat every problem you encounter as a nail. Becoming PeopleWyse means raising children’s awareness of the tools in their mental toolbox, together with insights into which tool to use for any particular job.

Encouraging children to link ideas in increasingly sophisticated ways – i.e. to join up ‘little ideas’ to make more complex ones – turns disparate items of knowledge into information. Being able to look at ideas, experiences, problems etc. in a variety of ways keeps thinking flexible and fresh and dampens the tendency to use so-called ‘routine’ thinking skills. Such a tendency has been summed up in the idea that if the only tool you’ve got is a hammer you’ll treat every problem you encounter as a nail. Becoming PeopleWyse means raising children’s awareness of the tools in their mental toolbox, together with insights into which tool to use for any particular job.

The basic definition and principles of creativity we’re using empower children’s thinking right across the curriculum. Furthermore, developing children’s ability to think more clearly and flexibly is not an add-on to all of the other things we are expected to do in the classroom. Rather it is an approach that complements the acquisition of knowledge and the mastery of other skill-sets such as literacy and numeracy. Ultimately, a creative thinking agenda will benefit children regardless of how prescriptive and content laden the curriculum happens to be.

Creative thinking can be introduced and developed by encouraging children to ‘be nosey’ – by noticing things and by asking questions. These behaviours generate the raw material that can then be linked and looked at from a multiple perspective.

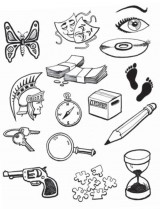

Fig.1 presents the class with a selection of objects that have been chosen at random. The simplest way of using the illustration is to invite the children to choose two objects and make a reasoned link between them. So –

• the watch and the hourglass because they both measure time

• the Roman helmet and the gun because they are both used in war

• the box and the jigsaw puzzle because they are both mysteries

These responses came from a mixed ability Y5 class. The third one is a more abstract link than the previous two, so demonstrating that creative activities can be used across a wide age and ability range. It’s usually not necessary to differentiate the materials: differentiation occurs at the outcome stage, with the children’s own responses.

These responses came from a mixed ability Y5 class. The third one is a more abstract link than the previous two, so demonstrating that creative activities can be used across a wide age and ability range. It’s usually not necessary to differentiate the materials: differentiation occurs at the outcome stage, with the children’s own responses.

You can extend the game in several ways:

• Ask for a reasoned link between three items, then four, five etc. Invite the children to bring in an image that can be added day by day to the selection. This sustains interest in the activity and raises the creative challenge. Consider using the linking game as a warm-up to your lessons: it primes the children to look for meaningful links between the ideas you present to them and encourages and strengthens the reasoning process.

• Prioritise the items in various ways; for instance in terms of how important they are on an individual level. This can lead to the exploration of personal values. Consider for instance the difference in values between a child who puts the butterfly at the top of the list and her friend who puts money first.

• Introducing and revisiting metaphor. By Y5-Y6 many children are able to think metaphorically; understanding that an object can represent an idea beyond itself (as demonstrated by the child who said that the box and jigsaw puzzle both represent a mystery). So, for example, the comedy-tragedy masks can represent our emotions, or the idea that our moods and feelings can change quickly; or the notion that we sometimes hide our true feelings. The CD can represent memories insofar as it holds stored information. The jigsaw pieces might stand for confusion, human ingenuity, the determination to reach a solution etc. Links like these become important again later on in teaching children coaching skills and ‘PeopleWysdom’ more generally.

• You might also use the images in a story making game. Ask the children to pick two items from the selection. If they were going to use them both in a story, what would that story be about?

Ask for the basic idea to be summarised in one or two sentences. What usually happens then is that another child takes up the challenge and says he can link three items. His friend very quickly claims to be able to link four. Thus the children raise the creative challenge for themselves, using the energy of competitiveness in a positive and creative way.

Giving someone your full attention is a key element of the coaching process. The ‘power to pay attention’ also develops children’s self-awareness, an important aspect of any emotionally intelligent behaviour. There are any number of attention games you can try out. Here are a few that we like.

Giving someone your full attention is a key element of the coaching process. The ‘power to pay attention’ also develops children’s self-awareness, an important aspect of any emotionally intelligent behaviour. There are any number of attention games you can try out. Here are a few that we like.

• Tell the children that you will be changing something about your classroom each day for the next week – who will be the first to notice what has changed when the class comes in next morning? You can pitch this at any level of subtlety, although we’ve found children enjoy easily spotting big differences initially and then increasingly subtle ones.

• Ask children to sit quietly, close their eyes and imagine the room they’re in. Ask them to remember one or two details. Pick a child and invite her to tell you all what she has remembered: the rest of the children are likely then to incorporate those details into their own imagined scenario. Then ask for volunteers to add their details. After several minutes tell everyone to open their eyes and compare their imagined classrooms with the real one. Quite a number of children are likely to be surprised at how little they remember. Suggest to them that they can deliberately notice more things over the coming days, so that when you do the noticing game again their imagined rooms will be much richer.

• Use video clips or still images of people. Ask what emotions they are displaying, what mood they’re in etc. Then say ‘And what clues do you notice that give you this idea?’ Draw out as much detail as you can about the subjects’ body posture, facial expression and so on. If the children enjoy miming and role play get them to mimic sadness, happiness, irritation etc. while their classmates notice how they do this.

• Ask children to sit quietly with eyes closed or staring at the floor. Explain that we can all direct and focus our attention. Tell them to –

– Notice the weight and position of your body in the chair.

– Notice the position of your hands.

– Notice the feel of the floor underneath your feet.

– Notice any tension in your shoulders. Relax your shoulders.

– Notice your own breathing (without trying to change its rhythm).

– Notice how still you can be for the next five breaths.

This is a wonderfully calming activity that can also be used to quieten the class after vigorous movement, and as a preparation for further learning when their attention is required.

This is a wonderfully calming activity that can also be used to quieten the class after vigorous movement, and as a preparation for further learning when their attention is required.

Ideas in this article first appeared in Coaching Emotional Intelligence in the Classroom (2010) by Steve Bowkett and Simon Percival, published by David Fulton Books who have given their kind permission for material to be reproduced. Artwork by Tony Hitchman.

Ask children to delve a little deeper…

The story making game described in activity 1 is useful for prompting children to ask questions and give reasons. When a child says ‘I pick the masks and the money. A guy puts on a mask and goes to steal some money,’ ask further questions such as –

• Why is he stealing the money?

• Where is the money now?

• How does he hope to get away with it?

• Who else is involved in the incident?

• What happens next?

This game begins to demonstrate the power of open questions and implicitly at first (although you can make it explicit) shows that different open questions elicit different kinds of information.

We call ‘because’ a sticky word. Whenever a child uses t she needs to stick a reason on the other end. Reinforce the idea through having reasoned arguments and debates in the classroom. As appropriate, when a child expresses an opinion ask for more – ‘And you believe that because…?’

Steve Bowkett is a full-time writer, storyteller, educational consultant and hypnotherapist. He is the author of fifty-five books including the Countdown to Writing series for Routledge. Simon Percival is a former teacher who as a qualified and experienced coach now runs his own practice helping individuals, including students, reach their personal and professional goals. Steve and Simon offer ‘PeopleWyse’ workshops to children and training for teachers in creative coaching techniques.

How To Use Books To Help Children Cope With Life

Ace-English