Ignoring objective setting in favour of Negotiated Assessment can help motivate children of every disposition, says Paul Dix...

When children assess themselves against criteria that they have set, they become engaged and motivated. Setting objectives for your class has little tangible effect on engagement or achievement, but the opposite is true of negotiating success criteria. As such, the Negotiated Assessment Grid (NAG), which is firmly based in educational theories and successful classroom practice, has far reaching possibilities. It’s not rocket engineering; it’s more a synthesis of what we all do already but brought into a clear and usable conceptual framework and method.

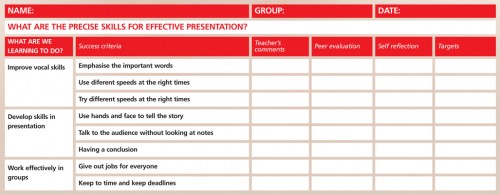

At the core of this model for assessment is a simple grid. Drawn on paper or projected on the board, it frames the ideas and defines the negotiated agreement. There is nothing flash or difficult here: the NAG works as well with analogue teaching (large sheets of paper and thick pens) as it does with digital technology, and it is flexible enough to be used in any subject and with any age group. It is quickly understood and easily owned by the children.

Successful classroom assessment starts with the right model. Provide an interesting model for the class before you collect any ideas – an outstanding piece of work from last year’s class, a video clip, reading or practical demonstration or an imperfect attempt from the teacher, for example. Your key question focuses the class and allows them to deconstruct this model and create their own success criteria. It forces them to imagine a successful outcome, like the 100 metre sprinter who sees herself on the podium.

Try

• What are the elements of a fantastic story?

• What are the skills of estimation?

• What makes a good listener?

• What builds a believable performance?

• How do we learn to remember?

The question is designed to elicit accurate, focused success criteria. Collect in all of the responses, in the children’s own language and without rejecting anything. Very quickly you can establish the overarching themes of the lesson and broader success criteria for the task in column 1 (see overleaf). For younger children, agree an icon that will represent these ideas alongside the words. A vital part of the process of negotiating criteria with the students is an acceptance of the language they use: verbal and visual. It will be tempting to substitute their language for the subject specific language, or with more academic terms. By accepting their own language we accept the way they think, link it clearly to the work and so encourage immediate engagement.

Now that you have the broader criteria established, groups/individuals can use the master list to select finer criteria to place on their grids in column 2. It is this criteria that each group will be focused on during the task to the exclusion of all others.

Now that you have the broader criteria established, groups/individuals can use the master list to select finer criteria to place on their grids in column 2. It is this criteria that each group will be focused on during the task to the exclusion of all others.

When the criteria are established, make a point of reflecting the ideas back with, ‘Whose ideas are these?’ Children will slowly respond with a, ‘They’re ours’, and begin to realise that you are passing responsibility to them. Some may even sit forward in their chairs. Develop engagement by reinforcing the knowledge and understanding that they bring to the task. Raise expectations by convincing them that they should have confidence in this work – after all they have already established the same criteria as a fully qualified teacher! This is particularly pertinent for those pupils with poor writing skills, or your Y3 boys who would rather wriggle than write. Convince them that they are in control and have a great deal to contribute, and you start to redirect negative thoughts and behaviour while focusing the learning.

Now pull out your learning objectives that you diligently prepared, compare them to their suggestions in column 1 and be amazed each time just how close they are. ‘So if I am supposed to be the expert in this and you have chosen the same criteria, what does this say about you?’...‘Yes, you are intelligent. I have been teaching this for 2/8/38 years, and you seem to know exactly what is required.’

Through this process, you have successfully clarified the key vocabulary and learning objectives while differentiating for all abilities. In the corner of the room you see a nervous smile from the Ofsted inspector who lurks with an, ‘I’m not sure I can cover all of that with the limited amount of tick boxes I have’ look on her face.

So, with their minds organised, yet jampacked with ideas about how they can succeed in this lesson, the children rush off to their task. Is the NAG now dead? Not in the least. Both you and the class can use it further.

During the task students can be keeping their own and their groups’ work focused by referring to the NAG to gauge their successes and target areas for improvement. Leave the grid by the side of the working area, and groups will naturally use it as an aide memoir for the task. The teacher’s responsibility is to tour the room, adjusting criteria selection and making sure that children are challenging themselves but not setting themselves up to fail. Add one or two criteria of your choosing if necessary.

During the task students can be keeping their own and their groups’ work focused by referring to the NAG to gauge their successes and target areas for improvement. Leave the grid by the side of the working area, and groups will naturally use it as an aide memoir for the task. The teacher’s responsibility is to tour the room, adjusting criteria selection and making sure that children are challenging themselves but not setting themselves up to fail. Add one or two criteria of your choosing if necessary.

Your role in the room will change. Rather than leading the assessment from the front, you are a roving expert, delivering subtle guidance when and where it is needed. Note discrete feedback as groups work and you answer less and question more. Give groups time-outs for self reflection (column 4), moments to create five minute targets and rich questions to provoke their thinking. As the grid fills up, ideas and reflections are held. You have deftly created a written record of the process. Even really active work can be assessed, ideas held and targets bridged across lessons.

As the grid fills it becomes an excellent vehicle for peer assessment and peer discussion.

Marking and conversations are immediately more productive, as the focus has already been agreed. By swapping grids, groups are instantly given rich information for their assessments. They can see the product and the process in one. They can assess with more accuracy.

With the grid full of contributions from different perspectives, it also allows children to set meaningful targets for themselves: targets that come directly from the task; targets that are owned and understood; targets that are time and context related; SMARTer targets than might be held in the teacher planner?

Negotiated Assessment Grids work for a huge range of abilities and personality types. Less confident groups enjoy the structure, challenging groups are reminded of their responsibilities and more able groups relish the independence. With practice all children will be able to enter the room, find out what the task is and start to create their own grid.

Negotiated Assessment formalises that which is at the core of good teaching: creating frameworks that allow the children to take control of their own learning; deconstructing models and skills while empowering the class to succeed as reflective, autonomous learners. You might think that this ticks a lot of boxes. It does. But it comes from good practice that is proven to raise achievement, not from the inspector’s handbook.

Paul Dix is an award-winning teacher trainer, Behaviour Expert for Teachers TV and the TES, and managing director of Pivotal Education Ltd http://www.pivotaleducation.com. His new book, The Essential Guide to Classroom Assessment, has just been published by Pearson/Longman.

You can use your checklist (or grid) in different ways:

• Agree success criteria with the children using their own language in the first instance

• Agree clear guidance for the markers: how to mark, acceptable/unacceptable comments

• Let children mark work from past pupils. The markers can then compare their grading with actual grades and discuss variations.

• Focus on one success criteria and break it down into the constituent parts for intensive assessment of a single criterion.

• Display a number of pieces of work with children marking in teams. Each pupil will look for a certain aspect of the agreed criteria.

• Play ‘speed marking’ with teams in competition to find where the marks have been earned/lost.

• Try anonymous scripts to moderate the marking – research shows how the rank order of marking changes dramatically when teachers know which pupils submitted the work

If your marking doesn’t affect pupil progress - stop it!

Ace-Classroom-Support

Should you let educational researchers into your classroom?

Ace-Classroom-Support

Join the tribe with a stone age forest school

Ace-Classroom-Support