Encourage children's critical thinking with Will Ord's wellthought- out activities...

People who cannot think well for themselves are always open to exploitation as political citizens, consumers and workers. Being able to think skilfully, therefore, is not just an academic advantage but absolutely central to:

• Defending ourselves against bad arguments

• Developing our sense of right and wrong

• Justifying our beliefs, actions, values and opinions

• Expressing ourselves coherently to others

In short, an unthinking citizen is a puppet. No surprise, then, that the Citizenship Education Programmes of Study at KS3 comprise one section on knowledge and another two on “skills of enquiry and communication” and “skills of participation and responsible action”.

One major element of skilful thinking is that of reasoning. We could say reasoning has two sides to it: one is to do with the thinking skill itself, and the other is the attitude with which it is employed. That is, reasoning and being reasonable (or ‘able to be reasoned with’).

Reasoning

i.e. thinking through arguments, supporting opinions, ideas and values well etc.

Reason-able

i.e. able to be reasoned with; open-minded, fair, patient, good at listening, respectful, level headed etc.

If children are not helped to understand the basics of reasoning then they can easily fall into confusion about what is right and wrong. Typically they might say things like “There’s no right and wrong” or “We’re both right; we’ve just got different opinions.” Adults say these things too. We need to get this thinking clear.

Consider the question “Was Hitler wrong?” The usual confusion here is equating ‘difference of opinion’ with ‘equality of opinion’: the idea that different views are equally true, right or good. Why? Because we’ve assumed that ‘truth is subjective’, so what’s right for you is right, and what’s right for me is right too. This is the philosophical realm of moral relativism.

But what if our views are contradictory? For example, I believe it’s wrong to kill people on grounds of race. Hitler doesn’t. Does that mean “we’re both right”, that it’s just a matter of perspective? No!

Hitler was wrong. By saying that I mean that his idea of what is morally acceptable (right) is wrong! He may think he’s right, but I want to argue that the grounds for his belief – his reasons – are weak. Therefore his belief is wrong; it’s not ‘just another viewpoint’.

Put another way, my house (belief) is made out of bricks and mortar; Hitler’s belief is made out of wet sand. They’re both houses (beliefs), but they’re not equal in their quality or strength. One is strong – right – and the other weak or wrong!

To get to the heart of differences of opinion therefore, we need to scrutinise each other’s reasoning. We need to ask why we see something as morally good or bad. How many reasons support the two opinions, and are they strong or weak reasons? Whose reasons are better therefore? We should certainly not be turning away with our hands in the air claiming it’s “just a difference of opinion”!

Consequently, what children need is:

• The social and emotional context to be open about their views without fear, and a reason-able community or class that respects and tolerates each other well. But also…

• The tools with which they may engage with differences of belief, opinion, action, and values. In short, the ability to reason things through.

These are not separate items – one allows the other to develop. If we know there’s a clear and logical way of working through arguments (reasoning), we know things can be worked out fairly and calmly (reasonably!). If we experience arguments as a reasonable process, we can take more risks with our thinking.

The following activities should give rise to some good thinking and discussion about reasoning. The Reason Tree will help children understand that opinions (as well as actions, values, and beliefs) can be supported by both a number of reasons and reasons of differing strength, whilst ‘Diamond 9’ will help them explore what makes a reason strong or weak in more depth. Using them, children will be able to think more clearly and more in depth at home and at school.

Draw a tree with some roots. In the leafy area, write an opinion, preferably one that the child has said or holds – for example, “You should not eat meat”. Now consider what the ‘roots’ of the tree might be – that is, what are the reasons for that opinion (what is holding the opinion up)?

Examples of the roots might be:

• It’s cruel to kill animals

• We can survive without eating meat

• Breeding cattle is bad for the environment

• It’s healthier for us

• It’s expensive and you could save money

You could discuss whether some of the roots are deeper or thicker or stronger than some of the others – i.e. are some reasons seen as better than the others, or are they all equally strong? (As an extreme example, consider the following: Arsenal is a good football team because (a) there are elephants in Africa or (b) the team has very skilled players. Clearly (b) would be a very thick deep root compared to (a) which is hardly a reason at all!)

Now consider the winds! These are the reasons against the opinion (they’re trying to blow the opinion down). In this case they might be:

• We’ve always been hunter gatherers; it’s natural

• We need meat as part of a rounded diet

• Animals can be kept in very good conditions

• Animals can be killed painlessly

• Meat is very tasty and enjoyable

Once you have both mapped out reasons for and against (roots and winds), explore what you think happens to the tree. Is it blown over by the very strong winds, and not supported enough by the weedy roots? Is it hardly affected by the winds at all because the roots are so deep? Or is the tree bending over to some degree, showing that there may be good reasons for and against?

Once you have both mapped out reasons for and against (roots and winds), explore what you think happens to the tree. Is it blown over by the very strong winds, and not supported enough by the weedy roots? Is it hardly affected by the winds at all because the roots are so deep? Or is the tree bending over to some degree, showing that there may be good reasons for and against?

The Reason Tree allows children to see that an opinion is not simply right or wrong, but may have good reasons for and against it. This helps them to be a bit more open-minded when discussing things – that is, to be more reason-able!

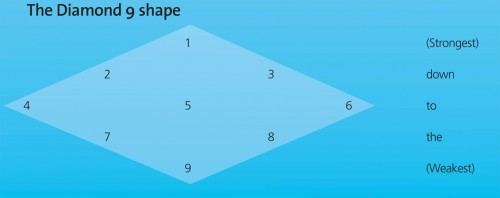

Deciding whether a root or wind is ‘strong’ or not is quite tricky. It can be hard to see that reasons differ in strength, and for different reasons! For example, a reason might be morally strong or weak, logically strong or weak, practically strong or weak etc. The following ‘ranking exercise’ will help this point become clearer.

The scene is this: someone has stolen some bread. Stealing is bad, but before we judge too quickly, we should look at the reasons why somebody might steal. How could they justify their action? The nine squares below each have a possible reason that a person might give for stealing some bread.

• Make copies of the nine squares below.

• Ask your pupils to put the nine squares in the diamond shape (see below). Let them decide which was the strongest reason for stealing the bread (top position), then the two next best reasons (second row), and so on down until they have the weakest reason at the bottom.

9: I stole the bread because…

• I was bored

• I didn’t have any money on me, but I felt like a snack

• My sister was hungry and we are very poor

• I would be bullied by some boys for ‘being a chicken’ if I didn’t

• like the thrill of taking a risk

• All my friends were doing it too

• It was a hot Tuesday afternoon

• The shop keeper was rude to me last week

• There’s no risk! I’m too young for the police to be involved if I get caught anyway

Pause for a moment. Ask them what the exercise has shown them about reasons, or ask them more directly: “Are all reasons equally strong?” Their answer (“no”, hopefully!) is important. Why?

If reasons are not all equally strong, then it follows that the opinions / values / beliefs / actions they justify are not ‘all equal’. Some opinions, for example, will be better than others because the reasons behind them are stronger. Make this really clear to pupils!

It is this realisation that will help children to see that having a different opinion is not the end of the thinking or discussion. It’s not a matter of saying “Oh well, we’re both right in the end, I guess”, or “Well there’s no right or wrong”. It’s a matter of getting underneath the opinions and seeing if they are well-reasoned (supported) or not. This allows the thinking to delve into much deeper levels of sophistication.

Share and model useful ‘thinking’ words with your class…

During lessons, see if you can:

• Use the words of reasoning to help children gain the vocabulary they need: reason, conclusion, justify, premise, argument, explain, agree, disagree, fair, if, then, because, etc.

• Ask questions that search out reasons for something. For example: “Why do you think that?”, “What supports that view?”, “Is that a strong reason for…?”, “What might the reasons be for that?”, etc.

• Give examples of your reasons for your opinions, actions, beliefs or values. Try to avoid just stating your view without explaining why you think it. This models the language and the concepts of reason giving.

Discover more on philosophy, citizenship education and RE at thinkingeducation.co.uk

How To Use Books To Help Children Cope With Life

Ace-English

Use the bottle-flipping craze to create good school behaviour, not bad

Behaviour Management

Behaviour management: choosing the right words

Behaviour Management