Stephen Bowkett introduces a story making aid to enthuse, encourage and educate children in equal measure...

The idea that a story has a beginning, a middle and an end is something that children understand from an early age. It’s built into the way we make sense of things. We think of the past as being behind us and the future ahead of us, while our immediate presence is, well, in the present. Such a timeline forms the basic template for the way we organise our lives and construct our stories. It’s also the underpinning rationale for the use of story strings.

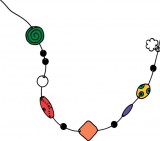

A story string is simply a number of beads threaded along a cord. The beads may either be chosen at random or deliberately selected and sequenced. Story strings can be of any length with as few or as many beads as you like. The beads themselves can be literal representations of objects – a clown bead is simply a clown, for example – or more symbolic. So, for instance, a round, red bead could be the sun, a drop of blood, anger, etc. This means that story strings can be made to suit children across a wide age and ability range.

A story string is simply a number of beads threaded along a cord. The beads may either be chosen at random or deliberately selected and sequenced. Story strings can be of any length with as few or as many beads as you like. The beads themselves can be literal representations of objects – a clown bead is simply a clown, for example – or more symbolic. So, for instance, a round, red bead could be the sun, a drop of blood, anger, etc. This means that story strings can be made to suit children across a wide age and ability range.

The immediate learning benefits of story strings are:

• They bring a tactile dimension to the process of story making. A child will literally handle their way along the story-line, constructing the narrative as they go by passing the beads through their fingers. The child is ‘telling’ the story; the word tell having its roots in the Old English tellen ‘to count’ as in a bank teller; and the related word talu (again Old English) meaning ‘tale’. We have for thousands of years been telling tales – and, significantly, it’s almost impossible not to use one’s hands in the process!

• They encourage creative and symbolic thinking. Our language is underpinned by metaphor. The things we say and write are very often not literally so. When I’m annoyed I don’t actually blow my top. If I’m hungry I probably couldn’t in fact eat a horse, and so on. Although children tend to grasp this in a tacit or implicit, unspoken way, deliberately exploring the idea through what beads of different shapes and colours might stand for feeds their understanding.

• They develop concentration. The beads on a string invite handling, and when combined with your prompting and guidance (more on this below) a child will usually focus their full attention on the ‘story in hand’.

• They instil a sense of authenticity and ownership in the child of the ideas they generate. I think it’s very important that we don’t spoon-feed children too much, since this dampens the tendency for them to become independent and creative thinkers. The fact that any number of stories are suggested by a story string offers flexibility within a structure – a fundamental principle in developing thinking skills – by allowing a child to make up their own narratives through the material that we’ve supplied.

A quick and simple way of introducing story strings to your class is to begin with a couple of ‘literal’ beads. Photograph and project them side by side and say to the class, “If you used these two things in a story, what could the story be about?”

So, if we used a bear bead and a flower bead responses might be:

• The bear went out to pick some flowers.

• The bear was looking for a special flower.

• One day the bear woke up and saw that a flower had grown outside his window.

Each of these represents a ‘creative connection’ that a child has made between the two, initially disparate, objects. You can now begin to elaborate on the basic ideas by asking some open questions. Why was the bear picking flowers? What was special about the flower the bear was searching for? How had the flower grown so quickly outside the bear’s window?

In answering these questions the children are immediately engaged in the process of story making.

Children’s responses will tend to reflect the arrangement of the beads left to right. Try putting the flower before the bear and see what new ideas are generated because of this.

Extend the game either by swapping the beads one at a time, gathering ideas at each swap, and/or adding a third bead, then a fourth, etc. The children’s narratives will naturally become more elaborate, and they will enjoy the creative challenge as you make the bead sequences longer.

Extend the game either by swapping the beads one at a time, gathering ideas at each swap, and/or adding a third bead, then a fourth, etc. The children’s narratives will naturally become more elaborate, and they will enjoy the creative challenge as you make the bead sequences longer.

Begin using beads the children must interpret, i.e. beads that prompt symbolic thinking. Using flower bead, for example, ask the question “What could this be? What does it remind you of?” Children will quickly realise that the bead could be any number of things, and that answers are not necessarily right or wrong.

When the children are comfortable at this stage of thinking you can move on to the use of story strings proper.

Story strings can be used for a group work, especially if you’re able to make several strings that are identical, since it’s important that each child should handle the beads. Or, of course, work one-toone. As I mentioned above this creates a particularly focused state of concentration in the child.

Teacher: So this first bead, what could it be?

Sarah (handling the bead): Well it’s green and swirly. I think it could be a whirlpool. Yes, it’s a whirlpool in the sea.

Teacher: That’s a dramatic opening to your story. OK, so these two little black beads…

Sarah: Um, well they could be two people in the water. Yes, they’ve fallen overboard and – they’re getting sucked into the whirlpool. Oh (sudden idea) and the black beads could also be two nights – the two people have been floating in the sea for two nights!

Teacher: Then what happens? That white bead…

Sarah: Could be an iceberg… No, I want this to be a pirate story, so the water is warm… OK, it’s a white boat. A boat comes along and rescues the people.

Notice how Sarah’s story making is spontaneous and natural. She was actually enjoying it too – and not stringing her teacher along at all.

• Prompt and guide rather than spoon-feed ideas. Ask open questions. A useful question is always “What could it be?”

• Prompt and guide rather than spoon-feed ideas. Ask open questions. A useful question is always “What could it be?”

• to the child that they don’t need to use every bead. If they get stuck, just suggest they move on to the next one – “And what could this bead tell us about what happens next?”

• Use the same story string with a variety of children and ask them then to share their tales. Let each child handle the story string during their retelling.

• Once a child becomes more confident in using the strings, give them one they’ve handled before, but this time turn it around and start from the other end.

Ideas in this article first appeared in Developing Literacy and Creative Writing through Storymaking (2010) by Steve Bowkett, published by Open University Press who have given their kind permission for material to be reproduced.

Pie Corbett’s bike poems

Topic

5 friendship and emotions intervention ideas

Ace-Classroom-Support

Use the bottle-flipping craze to create good school behaviour, not bad

Behaviour Management

How to use modelling to engage pupils with autism

Ace-Art-And-Design