Don't expect children to write before they can talk, counsels Sue Palmer – let the words flow out before they're committed to paper...

Several years ago I asked a group of 10- year-olds which was harder – talking or writing. They looked at me as though I was mad:

“Writing, of course.”

“Why?”

They came up with the answers you’d expect: writing makes your arm hurt, you have to spell the words, put in the full stops, and so on. But one little lad, obviously the class philosopher, gave a more considered response.

“Well, talking’s easy,” he said. “You open your mouth and the words sort of flow out. But when you write, you have to get a pen, and a piece of paper, and then… and then you feel really tired.”

I knew exactly what he meant. I’ve been a professional writer for 25 years, so no longer suffer from arm-ache or anxiety about secretarial skills. But I recognise only too well that feeling of exhaustion when I sit down to start a new piece of writing. Putting words together to make sense to an unknown, unseen audience is desperately hard work, even when you’ve had loads of experience. For an inexperienced writer, still struggling with handwriting, spelling, punctuation and sentence construction, it’s a mammoth task.

So, the least we can do to help is make sure that – once they’ve found their pen and piece of paper – our pupils know exactly what they want to say. And since talking comes naturally to all human beings, that means giving them plenty of opportunities to ‘let the words flow out’ before they’re expected to write them down.

Two horses before the cart

Two horses before the cart

In fact, especially in the case of writing across the curriculum, expecting pupils to write something down before they’ve talked it through is definitely a case of putting the cart before the horse. How can they write until they’re confident with the relevant vocabulary, clear about the underlying concepts, sure of the content they need to record? The more active we can make their learning, the more they’ll talk about what they’re doing, and the firmer their understanding will be. Motivating, purposeful opportunities for talk are essential for genuine comprehension.

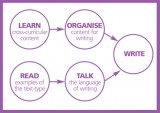

In the ‘two horses’ model (below), the top ‘horse’ covers this essential ‘talk for learning’. It has to take place in a meaningful curriculum context (as opposed to a literacy lesson), so it provides the perfect opportunity to link crosscurricular work to the teaching of non-fiction writing skills.

In the ‘two horses’ model (below), the top ‘horse’ covers this essential ‘talk for learning’. It has to take place in a meaningful curriculum context (as opposed to a literacy lesson), so it provides the perfect opportunity to link crosscurricular work to the teaching of non-fiction writing skills.

But talk for learning isn’t enough. Children need a second ‘horse’ to draw the writing cart. This is familiarity with the language patterns and conventions used to write particular nonfiction text-types. This sort of ‘literate language’ is very different from the language of spontaneous speech, and doesn’t naturally flow from the average child’s mouth.

So, children also need to engage in ‘talk for writing’ – directed activities to familiarise them with the literate language patterns they need before they start committing ideas to paper. This is the stuff of literacy teaching, and provides the opportunity to link non-fiction text-types to work across the curriculum.

Talk for learning

Talk for learning

It goes without saying that ‘active learning’ keeps language flowing more productively than passively listening to a teacher or staring at a whiteboard. Field trips and outings, investigations and experiments, drama and role-play, opportunities to make models (or displays, exhibitions, ‘broadcasts’, animations, websites, etc.) or to stage presentations of various kinds all inspire talk for learning. So, do open-ended group or class discussions and provide regular opportunities for paired talk about issues that arise as they learn.

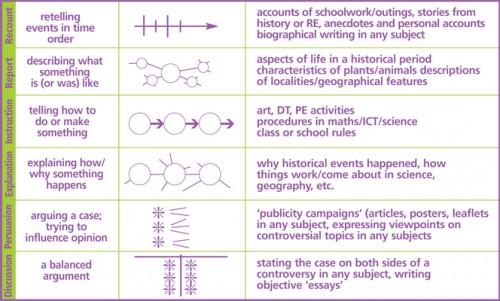

Once pupils are thoroughly familiar with the content, it helps enormously to organise their understanding before they write. The skeleton planning frameworks I devised while working for the National Literacy Strategy (below) provide a link between cross-curricular content and non-fiction text types. Working in pairs to plan their writing on a skeleton framework not only makes pupils’ thinking visible and portable (so they can transport it to their literacy lesson from Geography, History, Science or cross-curricular topic) – it also provides another opportunity to talk through the content as they shape it into the most appropriate form for writing.

The six non-fiction text types and their application across the curriculum

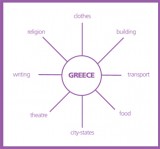

For a history project, a Y5 teacher asked pairs of children to choose and research one topic from a spidergram about Ancient Greece, with a view to:

For a history project, a Y5 teacher asked pairs of children to choose and research one topic from a spidergram about Ancient Greece, with a view to:

• preparing a talk for the class

• making some sort of artefact to illustrate their talk

• writing a section for a class book on ‘The Greeks’.

To help them, she herself was going to model the whole process from beginning to end. She chose the topic of ‘buildings’ and, as she found out about it, decided to make a model of the Parthenon to illustrate her talk.

• read and browse around the subject

• brainstorm information to decide on categories for a spidergram

• read more carefully to make notes on her spidergram

Pupils followed the teacher’s model to produce spidergram notes on their own topics, working in pairs. The illustration below was one pair’s fourth draft. As they found out more about the subject, they cut and pasted their notes and felt increasingly confident about using key words or pictures as ‘memory joggers’ for their talk and writing.

Pupils followed the teacher’s model to produce spidergram notes on their own topics, working in pairs. The illustration below was one pair’s fourth draft. As they found out more about the subject, they cut and pasted their notes and felt increasingly confident about using key words or pictures as ‘memory joggers’ for their talk and writing.

They decided to illustrate their talk by making a chiton.

Meanwhile, the class studied samples of report text (non-fiction books from the class library), discussing the effects of:

• layout, especially headings, subheadings and captions

• language features – the teacher especially drew their attention to impersonal and formal language constructions, such as the use of third person pronouns and the passive voice.

The teacher showed how to give a prepared talk, using her skeleton notes as a prompt and illustrating aspects of her talk with reference to her model of the Parthenon. Pupils then gave their own talks, each member of the pair speaking alternately to cover one ‘blob’ of their spidergram notes.

The teacher demonstrated how to expand her skeleton notes into an illustrated double page spread for a class book (“I’m going to turn my memory-joggers into sentences and leave a line between blobs on the spidergram”). She drew particular attention to the layout and language features the class had noticed in their study of report texts. Pupils then made their own double page spreads, and a number of books on the Greeks were compiled, with copies for every contributor.

Now in updated second editions, Sue Palmer’s How to Teach Writing across the Curriculum: Ages 6–8 and 8–14 provide practical suggestions for teaching non-fiction writing skills and linking them to children’s learning across the curriculum. With new hints and tips for teachers, and suggestions for reflective practice, these books will equip you with all the skills and materials needed to create enthusiastic non-fiction writers in your classroom.

Now in updated second editions, Sue Palmer’s How to Teach Writing across the Curriculum: Ages 6–8 and 8–14 provide practical suggestions for teaching non-fiction writing skills and linking them to children’s learning across the curriculum. With new hints and tips for teachers, and suggestions for reflective practice, these books will equip you with all the skills and materials needed to create enthusiastic non-fiction writers in your classroom.

The books are available to order now from David Fulton Books at routledge.com/9780415579902 and routledge.com/9780415579919 respectively.

Outstanding schools: RJ Mitchell Primary

Outstanding schools

How to use Harry Potter to engage high-ability learners

Ace-Languages