Identifying creatively gifted children can be difficult. But if we don't, there's a risk these pupils will opt out through boredom...

Creativity is an area in which gifted and talented pupils often excel – given the opportunity. However, it is an extremely difficult concept to define and subsequently to measure. Creativity is not necessarily correlated to intelligence and research shows that over an IQ of 105 (just above average) there is no correlation between the two. This does not mean to say that an intelligent child cannot be creative, of course, and visa versa.

When it comes to testing for creativity I recommend the Urban and Jellen Tests (Urban and Jellen, 1996), which are now being used in many schools. In this assessment, in order to achieve a high degree of cultural fairness, a drawing test of figural stimuli is used. However, I have devised a much simpler three step test to indicate if a child has creative ability which is suitable for younger children as well as secondary school students.

1. To begin with, simply ask children what they think the term ‘creativity’ means. You may well be surprised by their answers…

1. To begin with, simply ask children what they think the term ‘creativity’ means. You may well be surprised by their answers…

2. Get them to list (in three minutes) as many possible uses for a brick as they can. On other occasions it could be uses for a wire coat hanger or a paperclip. Some bright juniors I worked with once recorded 38 different uses for a paperclip.

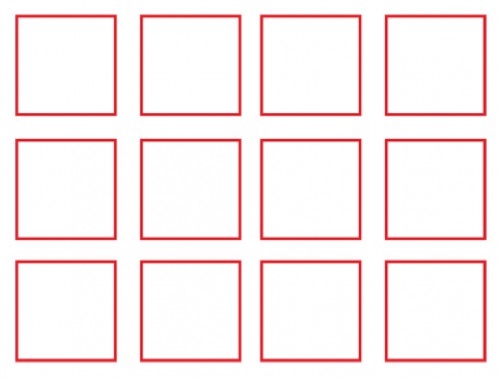

3. Ask children to use their imagination and make something creative using the twelve squares over the page. Give them five minutes for this.

By asking children to discuss the meaning of creativity first, they are then, hopefully, in a position to produce something creative out of twelve squares. In my experience 92 per cent of children tested confine their drawing to inside the boxes, whereas just 8 per cent think quite differently and make whole pictures and/or think outside the box.

The following are examples of children’s responses to this exercise.

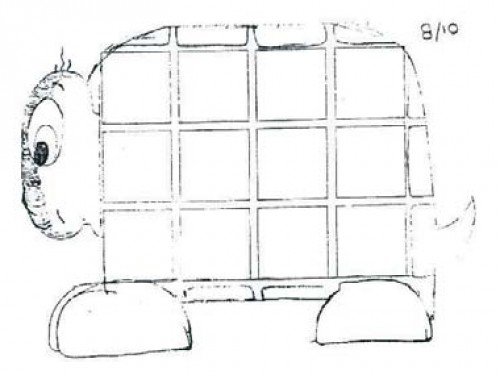

It is the professional duty of busy teachers to spot talent when they see it. Gifted children are not always consistent in the work they produce, but if they are motivated they can perform exceptionally well. There follows two pieces of work by outstanding children which I suggest indicate an advanced ability (and I am not referring to KS levels!). How would you assess this work?

During a topic on dinosaurs by 6-year-old infants the teacher asked the children how they could solve the problem of cleaning a dinosaur’s teeth. This is Daniel’s creative solution.

During a topic on dinosaurs by 6-year-old infants the teacher asked the children how they could solve the problem of cleaning a dinosaur’s teeth. This is Daniel’s creative solution.

A man climbs the dinosaur’s back to its head, where he dangles food in front of his eyes to open its mouth. Another person on the houseroof cleans the dinosaur’s teeth with a brush. The person on the ground is putting glue down to keep the dinosaur still. He is wearing a mask because the glue is poisonous. – Daniel

Elizabeth, aged 12, took a different approach from the rest of her class when they were asked to write an essay on conflict.

Conflict Surprise (a recipe for war)

Ingredients:

5kg of greed

2kg of envy

1 raw anger

1 large selfish (very ripe)

5g of mistrust

7kg of overripe violence

3 large misunderstandings (if you have them)

Method:

Using a fist, mix in the greed and envy. Let it simmer for an hour. Kick the raw anger in. Squeeze the selfish and add it to thicken the mixture. Sprinkle the mistrust and stir thoroughly. Using a tank (if you have one) firm in the violence. Beat in the misunderstandings. Take a world leader and empty its mind of peaceful thoughts. Using half the mixture refill the mind. Carefully put the world leader back in its place. Using a sword spread the other half of the mixture across one of the world’s countries. Remember to stand back after you have done this; you may become a victim of your own creation. Watch for the after-effects. You will enjoy the pain and suffering. You will find it impossible to clean the kitchen when you have finished; all the ingredients will contaminate the rest of the kitchen. Quick tip: for fuller flavour, act first, think later.

The following are some questions I have been asked recently:

• A 6-year-old asked me if God made the world, what did he stand on?

• An 8-year-old asked, why do brown cows eat green grass, and give white milk?

• A 10-year-old asked me, how do you know when you know? This question, I suggest is at about BA Philosophy level, and you could almost hear Plato posing the problem.

From questions such as these, it is clear that every child is unique and displays his or her giftedness – or in the case of our gifted underachievers, conceals it – in a variety of ways. For this reason it is difficult to define the concept of giftedness or to describe general characteristics according to which a child could be classified in a specific category. It is obvious that a distinction must be made between specific and general giftedness, between intellectual/academic and specific talents, as well as between different kinds of giftedness. It is also understood that we must look at a much wider talent pool and recognise that giftedness is the potential for exceptional development of specific abilities as well as the demonstration of performance at the upper level of a talent continuum. This is not limited by age, gender, race, socioeconomic status or ethnicity.

Unless a child’s abilities are known and carefully assessed, he or she cannot possibly receive – except quite fortuitously – the programme of work and degree of challenge he or she needs. If our gifted children are to receive social justice within our school system, we owe it to them to identify them and adapt the curriculum to suit their needs and thus prevent any likelihood of them opting out through boredom, frustration or lack of recognition.

Extract taken from Young Gifted and Bored by David George, edited by Ian Gilbert (Crown House Publishing 2011) © David George ISBN 9781845906801, part of the Independent Thinking Series of Books. crownhouse.co.uk

Extract taken from Young Gifted and Bored by David George, edited by Ian Gilbert (Crown House Publishing 2011) © David George ISBN 9781845906801, part of the Independent Thinking Series of Books. crownhouse.co.uk

Dr David George is Founder President of the National Association for Able Children in Education and was a member of the Executive Committee of The World Council of Gifted and Talented Children. He is a consultant to the British Council and UNESCO. He has lectured both nationally and internationally on the education of gifted and talented children.

Join the tribe with a stone age forest school

Ace-Classroom-Support