Reading to children is hugely important, but reading to them well can create lifelong lovers of literature, says David Waugh...

Reading to children is hugely important, but reading to them well can create lifelong lovers of literature, says David Waugh…

I’ve often told my students that I wouldn’t be standing before them extolling the virtues of reading to children had it not been for Roald Dahl’s Danny. Back in 1976, my final school placement was with a ‘difficult’ class of 36 Year 4s (they were second year juniors then), and the teacher spent the first three weeks of my placement accompanying the three Year 6 classes on each of three residential visits, leaving me to try to manage her class. Fortunately, I had just discovered Danny, the Champion of the World, a retelling for children of a story Dahl wrote for adults in the early 1950s.

Over eight weeks, I managed to eke the story out, always ending on a cliffhanger and promising we’d have more soon – perhaps ending a maths lesson five minutes early so that we could discover what had happened to our hero and his father. It worked a treat. All I had to do if a group started to get noisy was say, “I don’t think we’ll be able to hear what happened to Danny today if that group doesn’t get some work done,” and peer pressure did the rest. The class managed itself and I passed my placement.

We discussed the story and the issues it raised. Danny is the hero, but he and his dad take Victor Hazel’s pheasants – is that right? Isn’t it stealing? Danny drove a car to rescue his dad from the trap in the woods – should he have done that? We even discussed corporal punishment (then legal in schools) and whether Danny’s teacher, Captain Lancaster, should have used the cane. The children also loved the idea that Danny wishes for, of an interesting fact appearing every day on the school wall, so they persuaded me to provide one for when they arrived each morning.

That placement left me committed to sharing literature with children and eager to find more stories to engage future classes. I have never since regarded reading to children as a luxury or a treat to be withdrawn if time didn’t permit. I tell my students that reading to children is one of the most important things they can do as teachers, but sadly, some do not see it as a priority.

How are children ever going to know what good reading sounds like if no one reads to them? How will they be able to enjoy stories where the language is more advanced than they could read independently if teachers don’t share such texts with them? And how will they know that books can bring joy, excitement and make them think, if their literary diet is limited to what they can read for themselves?

Last year, one of my students, whose Y5 class was proving difficult, contacted me and reminded me what I’d said about Danny and my final placement. She wanted to find a book which would engage them, develop their reading and make them think about important issues. Unfortunately, several of the children had already read Danny and she wanted other suggestions.

There’s no shortage of high-quality children’s literature, so I suggested Morpurgo, Pullman, Rowling, Walliams and others. To my surprise, she said: “What about that opening chapter you included in your book about children’s literature? I read that to them and they really wanted more. I don’t suppose you ever wrote any, did you?”

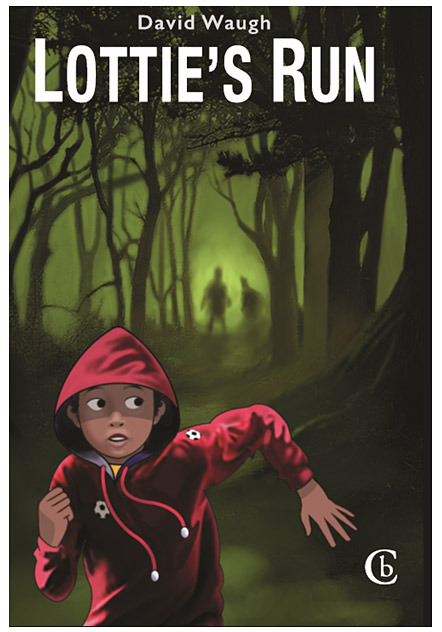

In fact, I had written a complete bedtime story called Lottie’s Run for my granddaughters a few years ago and the chapter was part of it. I’d used it in the book because there would be no copyright issues. I sent her the complete story and waited anxiously to hear how it had been received.

Within a week I’d been invited to the school so that the children could meet an ‘author’. I tried telling them I wasn’t that kind of author – “I write books about grammar and phonics, reading and writing. I haven’t published any stories.” It didn’t seem to matter. They wanted me to carry on reading it to them at breaktimes, and asked me to come back and read again. We did lots of hot-seating, retelling chapters in four lines of four words, discussing issues raised in the story, and writing predictions for how the story would unfold. The children produced newspaper stories about Lottie’s kidnapping and sent them to me. Their class teacher even told me that the children had been playing ‘Lottie’s Run’ in the playground. In the end, I felt I had to get the story published before the children left primary school. So this March, once it was published, I found myself back at the school signing copies of the book.

I’m no Michael Morpurgo or Roald Dahl, but the response of the children, and those in other schools where I’ve since shared the story, has certainly made me think a lot about the value of reading and discussing stories in schools. The power of stories to hook children who can read but choose not to should not be underestimated. Pisa (2011) showed that we have a greater number of children who profess not to enjoy reading than in many places, while Cremin et al (2008) found out that many teachers have a limited knowledge of children’s literature, which can have a knock-on effect on their pupils.

The best teachers I know read to their classes regularly. The rewards are immense in terms of literacy development, attitude to reading and the ability to infer and deduce meaning from texts. Good teachers support teaching across the curriculum by reading appropriate novels and poems to children, and PSHCE discussions are enhanced when dilemmas from books provoke discussion and argument.

And finally, reading a story to your class can be one of the best ways of forming good relationships and drawing them together for a common and pleasurable purpose. When I was a class teacher, after a hard afternoon, 20 minutes on the carpet finding out about William’s latest escapade or Matilda’s dreadful, grumpy headteacher put everything back on an even keel.

David’s book, Lottie’s Run, about the England football captain’s kidnapped daughter, is published by Constance Books.

What makes for an interesting an engaging voice at the head of the class? Here are some things to work on to develop your storytelling skills:

• Involve children through questioning and participation – it’s very effective in holding their attention

• Vary your voice tone, level and accent to engage children, and build up tension through facial expressions and pace

• Include artefacts such as those found in story sacks to help children to follow stories and hold their interest

• Manage time slots, both for yourself and pupils – read for too long and you’ll test their attention span, too short and they won’t have time to become engaged

• Be aware that some successful strategies will depend on age and and the class, while others will be more universal

Extracted from Children’s Literature in Primary Schools

by Waugh, D, Neaum, S and Waugh, R (2013), published by Sage.

David Waugh is author of numerous educational titles, and his first novel Lottie’s Run

is available in paperback or Kindle versions through Amazon.

Make every lesson an experiment

Cross Curricular

5 friendship and emotions intervention ideas

Ace-Classroom-Support