If pupils' ability to write doesn't match their ability to read, then creating better links between the two will see standards rise...

“What can I do to improve writing in my school? We regularly get a high percentage of pupils achieving level 4 and above in their reading, but it’s the writing scores which let us down.”

Is there a more common lament in primary schools? And what are we doing about it? A lot, is the obvious answer, but still the problem persists. In places where it does not, and writing scores rise, we are often left with the uncomfortablefeeling that children are not becoming better writers – they are simply being given credit for learning a few basic tricks: inserting an adjective here, an adverb or three there, often neither needed nor appropriate.

Against this background, the Professional Literacy Company (PLC) developed Good Readers Make Good Writers, a course which trains teachers in creating not only interested, reflective readers but resourceful and committed writers.

This series of articles aims to show you how we do it and introduce you to some of the texts that we use.

We know that good writers are invariably readers. We see it when we read children’s stories and discover words, phrases, whole sentences jumping out at us, giving clues to the books they are reading. We see it in the ‘book language’ they use when they write. And then there is that wonderful moment when a Y2 pupil unexpectedly writes a story in chapters because they’ve stumbled on The Owl Who Was Afraid of the Dark.

We know that good writers are invariably readers. We see it when we read children’s stories and discover words, phrases, whole sentences jumping out at us, giving clues to the books they are reading. We see it in the ‘book language’ they use when they write. And then there is that wonderful moment when a Y2 pupil unexpectedly writes a story in chapters because they’ve stumbled on The Owl Who Was Afraid of the Dark.

So if this is what good writers do – experiment with ideas they find in their own reading – what can we do for those children who are not committed readers, or who read as readers only, not as writers too?

We need to bring together the teaching of reading and writing. Too often we keep them separate, focusing on discrete skills but neglecting the whole experience. We need to recognise that young writers will only get better if they regularly hear the rhythms and cadences of written language read aloud with verve and expression. If they just draw on the patterns and vocabulary ofspeech, their writing will always be limited and stilted. That’s where shared reading and shared writing, using mentor texts, come in.

When we read to classes, we need to choose books that stimulate the mind and live in the memory. Serialising a book to a class went out of fashion for a while, a bit like role-play areas. When a resurgence took place, the books chosen were often tied in with topic choices or reflected limited knowledge of recent writing for children. No child should be deprived of Roald Dahl, and Goodnight Mr Tomis a great Second World War text, but there are other options.

When we read to classes, we need to choose books that stimulate the mind and live in the memory. Serialising a book to a class went out of fashion for a while, a bit like role-play areas. When a resurgence took place, the books chosen were often tied in with topic choices or reflected limited knowledge of recent writing for children. No child should be deprived of Roald Dahl, and Goodnight Mr Tomis a great Second World War text, but there are other options.

We all have our particular favourites, but some books work better than others as mentor texts. To get started, try running a staff meeting when teachers (and TAs) nominate their ‘austerity bookshelf’: if you were limited to a choice of three books, which would you share with your year group? Once you’ve cleaned the blood off the staffroom carpet, you will have a shortlist which will form your spine of mentor texts. As you refine your list, try to build in a sense of development, a range of genres and approaches to storytelling (use of time slip, shifts in point of view, formal and informal language) and some authors new to children (and teachers). This is the raw material young writers will be drawing on as they learn their trade.

When we read our mentor texts we should recognise the needs of readers who are meeting a text for the first time, and let them read as a reader. This means focusing on the experience, not stopping every few lines to ask comprehension questions or quiz on vocabulary. Let the words create pictures in the mind, place the reader at the scene, immerse them in the action. Periodically we can pause and talk about the experience – compare notes on what we see, hear, feel, think. Guided by Aidan Chambers’ wise advice about likes, dislikes, puzzles and patterns, we can draw them into ‘booktalk’ which is engaging, stimulating and non-judgemental, convincing them that we are interested in what they think, that their view matters. We can use role-play and hot-seating to explore why that irritating character did what she did, or what the character who kept his council really thought of events, but the narrative must never loosen its grip or lose its power.

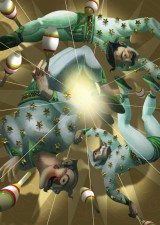

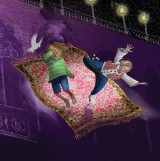

A taste from Leon And the Place Between:

A taste from Leon And the Place Between:

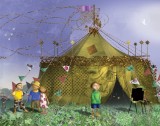

• Turn the role-play area into a storyteller’s tent. Use fabric, lights and music to create a truly magical atmosphere.

• Read Leon and the Place Between dramatically to the children.

• Once children have enjoyed the experience of the book, use Booktalk to explore their response, including questions dealing with…

- literal understanding: does the boy on the carpet live in the Place Between?

- inferential understanding: if not, why is he there?

- authorial intent: how do you think the crowd feel just before the curtains open?

- visual literacy: how do the illustrations add to the atmosphere of the story?

• Construct with children an oral telling of the story and create a story map. Involve children in the telling, using the map as a scaffold, until they are able to tell it independently. This embeds the structure and story language which they can then draw on in their writing.

Once children have thoroughly enjoyed the experience that the book has to offer the reader, we can re-visit the book selectively, looking at key episodes, only this time reading as a writer. Now we are looking to see how the author achieved his success, and picking up ideas we can practise for ourselves: magpieing, as Pie Corbett calls it. We can re-tell anepisode orally; box up a story to see how it works; assemble a toolkit of ideas for writing this way; try out a parallel version through shared writing and have a go individually. This is the essence of this approach: we don’t rely on the ability of one or two precocious talents to lift ideas to use in their writing, we teach all pupils how to grow as writers by using the example of others.

A taste from Leon And the Place Between:

A taste from Leon And the Place Between:

• Box up the story into sections e.g. The characters go to the show. The show begins. Leon goes into the magic box and is taken to another world. Events take place. Leon returns with a rabbit.

• Turn this into a generic version, e.g. Main character goes somewhere. Main character does something. Main character goes through a portal and is transported to another world. Events take place. Main character returns with a memento.

• The latter version can then be used as the basis for other stories. Demonstrate this to the class through shared writing before asking them to write independently.

• As you demonstrate, return to specific parts of the mentor text and explore how to use the author’s techniques when writing your own stories.

As children become familiar with a text, they will enjoy opportunities to springboard off the page into a wide range of potentially cross-curricular activities. They might create a podcast or a radio play, complete with sound effects, or produce an illustrated fieldguide to creatures found within the world of the book. The trick of course is to nsure that a book does not outlive its usefulness: that when we leave it, children’s memories of the book remain positive and strong.

A taste from Leon And the Place Between:

A taste from Leon And the Place Between:

• Set up a situation where Leon communicates with the class. This could be in the form of a letter or by using animation software such as Crazy Talk. In the communication, Leon tells the children that the magician, Abdul Kazam, has decided not to bring his magic show to town again because the audience was so small. Leon asks for the children’s help in designing and producing a poster that will persuade the townsfolk that the show is really worth seeing so that they will come in their hordes.

• Develop this narrative by creating a response from Leon saying that the posters are great, but now he’s having problems with the rabbit they brought home from the magic show. Could the children find out how to care for a rabbit, particularly one that vanishes, and send instructions?

• Leon is very excited in his next communication. The posters have been successful and Abdul Kazam has agreed to return. However, he wants to present each member of the audience with a special programme. Again, Leon needs their help … and so the narrative continues to unfold, providing a range of purposes and audiences for the children’s writing. The context is provided by their now in-depth knowledge and understanding of the book. Next month: Good Readers Make Good Writers in KS1 using Aristotle by Dick King-Smith.

• Leon and the Place Between by Angela McAllister is published by Templar Publishing.

• Tell Me: Children, Reading and Talk by Aidan Chambers is published by Thimble Press.

• Find contact details and more information about Good Readers Make Good Writers courses at http://www.theplc.org.uk

Gill Matthews is an independent literacy consultant and writer. She delivers INSET and speaks on many aspects of literacy both nationally and internationally.

Reorganise your music room

Ace-Music

Make World Book Day Extra Special This Year

Ace-English

Supporting parents with maths

Ace-Maths