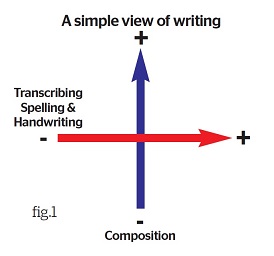

How many ‘reluctant writers’ have fluent, legible handwriting? This is not a rhetorical question: think about the children you are teaching or have taught and try to place them on this graph (the mid point of each continuum represents approximate age-related expectations.)

Do you find, or have you ever found, there are some children very definitely in that top-left corner? The ones who contribute really well during shared writing, and seem to have great ideas, but struggle to get these down on paper effectively? We have noticed that, by early KS2, many slow-to-no progress writers are in the position where their ideas – and their capacity to organise those ideas into sentences – substantially outstrip their spelling and handwriting.

Understandably, this may lead to feelings of frustration, low self-esteem, and general disenchantment with writing, which is tragic as sometimes these children can have the best ideas in the room. Thus, we might think of handwriting as the filter through which ideas must pass; you can have gold dust in your head, but if your filter is poor, what of the writing?

Could it be that the emphasis on lovely handwriting focuses too heavily on the prettiness of presentation, and too lightly on legible fluency? And would more boys have better handwriting if it were introduced as the filter for their plots and facts?

Conversely, some of the children in that bottom-right corner may be the ones who focus so intently on having perfect handwriting that they have little operational capacity left for compositional skills: their writing looks great, but the content is not engaging and the sentence grammar may lack ambition. These children too might benefit from the interpretation of handwriting suggested above.

Stepping away from the ‘remedial’ aspects of handwriting, is it not the case that virtually all of us, as educated adults, would find it hard to produce our best handwriting (or even spelling) in a first draft? The fact is, during a first draft, our operational memory – our ‘RAM’ – is taken up with matters of composition; a second draft is required to smooth out matters transcriptional, while also making adjustments to grammar and punctuation choices. In this transitional age, in which children and teenagers are still assessed in handwritten tests, yet most adults do most of their composing via a keyboard, it is easy for us to forget the fundamental importance of re-drafting in the writing process.

Many of the above points hint at solutions, but chief among these is the all-important Whole School Policy. If the goal is all children achieving legible fluency in their handwriting, then we suggest three key policy points:

Everyone believes that handwriting is vital in facilitating the communication of ideas (rather than just an attractive bonus).

Everyone – bar those with very specific needs – can achieve legible fluency (and if you wouldn’t accept that handwriting from a girl, don’t accept it from a boy).

You can’t change handwriting styles or schemes (or expectations) between year groups and expect the whole class to keep up.

There are many, many ‘top tips’ around the teaching of handwriting that sit within the points above, but these these are some of our favourites.

Think also of the children struggling in the bottom-left of our ‘extremely simple view of writing’. For them, doing it all at once is like learning to unicycle and juggle at the same time. Adults often scribe for these children (and it should be scribing, not turning their ideas into proper sentences: that’s the children’s job) as this allows them to focus on composition without worrying about transcription. We would suggest another step: that the adult then dictates what she / he has transcribed, and the children have to write this down. Now they are practising transcription without having to worry about composition. They will have authored the entire piece, but with the process scaffolded two ways. Eventually, they can be helped towards an independent version of this, whereby they compose into a recording device, then transcribe their composition as they play it back. (This usually works best if the child works sentence-by-sentence.)

And yes, we have avoided the debate about when exactly to introduce cursive handwriting. This is because we have noticed that schools (rather than individual teachers) that argue passionately one way or the other tend to have handwriting that supports composition, which itself supports the idea that consistency and commitment to handwriting are key.

Christine Chen and Lindsay Pickton are independent Primary Education Advisors, based in the Royal Borough of Kingston.

We do want to acknowledge that, for a tiny percentage of children, difficulty with handwriting is related to some very particular special need; we don’t, however, accept ‘being male’ fits into this category. Little boys very often do have good fine-motor skills when they want them – and if they’ve practised them. (They may not fancy threading beads onto a string, but try asking them to make a stegosaurus that will fit in a matchbox – this requires a lot of pinch-movements!) Be careful not to make excuses for boys and their ‘poor fine motor skills’, as they will cheerfully live down to those expectations. Years ago, a colleague pointed out to us that some of those terribly afflicted boys spent their weekends painting toy soldiers in incredible detail for their role-playing games…

Pie Corbett’s bike poems

Topic

How To Use Books To Help Children Cope With Life

Ace-English