It's time to rethink the way in which schools make use of support staff, say the Institute of Education's Peter Blatchford and Rob Webster.

Meet Reece. He joined Y6 at Dalebrook Primary in September. Reece has been assessed as having language delay, so twice a week he joins a small group of classmates to take part in an intervention programme. The intervention is delivered by someone that Reece has got to know well: Mandy.

Mandy is the teaching assistant (TA) in Reece’s class. She often sits with Reece in the classroom and supports his learning throughout the day. Deploying Mandy in this way is Mark’s idea. Mark is Reece’s teacher. As he feels he does not know enough about how to teach children like Reece, Mark thinks it’s useful for the boy to have additional support from Mandy, because she has more experience of helping children who have difficulties with learning. Mandy, like the other experienced TAs at Dalebrook, has been at the school longer than most of the teachers. Despite Reece’s learning needs, Mandy’s support seems to enable him to be included in a mainstream classroom, to access the same curriculum as his peers, and make progress academically.

Since the turn of the century we have seen an unprecedented increase in the number of teaching assistants in mainstream schools. They have more than trebled since 1997, and TAs now make up a quarter of the school workforce.

There are good historical reasons for this. Growing teacher workloads were leading to industrial unrest and worries about retaining staff. Schools also needed to cope with more pupils who had learning difficulties and special educational needs (SEN).

There was a general sense that the new army of TAs was doing the trick; teachers were happier and it looked as though SEN pupils were doing better – until our research threw a spanner into the works. Results first published in 2009 and described in our new book, Reassessing the Impact of Teaching Assistants: How Research Challenges Practice and Policy, raised concerns about the effect of TA support on pupils’ academic progress.

The vignette interspersed throughout this article characterises our findings, and focuses on a lightly fictionalised classroom and school.

Our five-year study, the Deployment and Impact of Support Staff (DISS) project, was the largest study of TAs worldwide. It measured the effect of the amount of TA support on pupils’ academic progress, while controlling for factors like prior attainment and level of SEN. Worryingly, our analyses of 8,200 pupils, across seven year groups, found that those who received the most support from TAs consistently made less progress than similar pupils who received less TA support.

These results are now widely recognised and have fed into the Lamb Enquiry on SEN, new Ofsted guidance and the Government’s SEN Green Paper. Some see TAs themselves as the problem and have suggested their numbers should be reduced. But in our view, this would be wrong. Other results from our project show that the fault is not with TAs, but with decisions made – often with the best of intentions – about how they are used and prepared for their work.

In today’s numeracy lesson, Mark spends the first half of the lesson teaching from the front of the class, then, as the pupils complete the worksheet, he roves around the room. Mandy’s default position is to sit beside Reece on red table, where they are joined by three other children with learning difficulties or special needs. Mandy is on-hand to explain concepts and instructions and to prompt the pupils in ways that Mark is unable to do from the front of the class.

The DISS study results stem from nearly 20,000 questionnaire responses from schools, teachers and support staff; hundreds of hours of extensive systematic classroom observations; transcripts of TA-to-pupil and teacher-to-pupil talk; over 1,000 TA work pattern diaries; and nearly 600 interviews with school leaders, teachers, support staff and pupils. Careful analysis of these results show where the true explanation lies.

The DISS study results stem from nearly 20,000 questionnaire responses from schools, teachers and support staff; hundreds of hours of extensive systematic classroom observations; transcripts of TA-to-pupil and teacher-to-pupil talk; over 1,000 TA work pattern diaries; and nearly 600 interviews with school leaders, teachers, support staff and pupils. Careful analysis of these results show where the true explanation lies.

First, the ‘deployment’ of TAs; that is, how they are used. The DISS findings show clearly that TAs today have a predominantly instructional role. There has been a drift toward TAs becoming, in effect, the primary educators of lower-attaining pupils and those with SEN. Teachers like this arrangement because they can then teach the rest of the class in the knowledge that the children in most need get more individual attention. But the more support pupils get from TAs, the less they get from teachers. Supported pupils therefore become separated from the teacher and the curriculum. It is perhaps unsurprising then that these pupils make less progress. The second explanation relates to the talk between TAs and the pupils they support. Detailed analysis of transcripts of classroom talk showed that when compared to teachers, TAs tended to focus on completing tasks rather than developing understanding, were reactive rather than proactive, and tended to ‘close down’ talk, rather than ‘open up’ talk cognitively and linguistically.

The third explanation connects with the first two: we found that that there were failings in the ‘preparedness’ of TAs and the teachers who worked with them. There is inadequate training for teachers on how to work with TAs, and a lack of opportunity for them to properly brief TAs before lessons.

The school relied a lot – albeit, it seemed, unintentionally – on the goodwill of its support staff.

Mandy felt a strong sense of duty to Reece and the other children she supported, and if it meant using her own time in order to ensure she could do right by them, then so be it. Take today for instance: getting in a little early to talk to Mark about the day’s lessons; preparing some resources for art in her lunch hour; staying behind after 3pm to feedback to Mark about, among other things, Reece’s struggle with the rounding off task in numeracy. In fact, if Mandy didn’t meet with Mark in her own unpaid time, there would be almost no opportunity for them to communicate at all.

The DISS project has shown that it is the children who need help the most who suffer most from the current methods of TA deployment. As Michael Giangreco in the USA has argued, we would not accept a situation in which children without SEN are routinely taught by TAs instead of teachers. So, it is vital we take this issue seriously. The present default position, in which pupils get alternative – not additional – support by TAs, lets down the most disadvantaged children.

So what is to be done? An extreme take could be to drastically cut the number of TAs, but headteachers and teachers repeatedly tell us that their schools would struggle to function without TAs. Schools do, however, find it tricky to demonstrate where TA support has improved pupil outcomes.

We agree that TAs could make a huge contribution to schools, but our view is that progress can only be made if we first recognise that there is a problem with the widespread forms of TA deployment, and then take steps to develop and evaluate alternative ways of using them.

We argue that encouraging headteachers to undertake a fundamental rethink of the purpose and role of TA is essential to fending off any accusations of wasteful expenditure.

To this end we have been conducting a follow up study, funded by the Esmée Fairbairn Foundation, in which we have been developing and evaluating strategies for improving TA deployment, practice and preparation. We have been conducting this work in collaboration with schools, using only their existing resources.

To date, the results of this research are extremely positive. Schools – with the support of school leaders – have beendeveloping alternative ways of using TAs. The findings from this study will be published later this year, along with a book containing guidance and strategies based on this work.

At a time when many schools are contemplating staff reductions, it should not be left to TAs to have to justify their position. But the budget cuts can provide the impetus for school leaders to seriously consider the added value they want to derive from expenditure on TAs, and find creative ways of making this happen.

Results from the five-year study, the Deployment and Impact of Support Staff (DISS):

1. Impact

1. Impact

There was a consistent negative relationship between the amount of TA support a pupil received and pupils’ progress in English, mathematics and science, even controlling for pupil characteristics, such as prior attainment and SEN status. This was found across seven age groups across primary and secondary years. There was evidence that the effect was more marked for pupils with a higher level of SEN, but it was still generally evident for pupils with no SEN.

2. Deployment

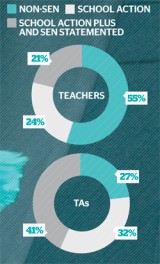

Which pupils are supported by teachers and TAs? (charts on the left)

Teachers tended to concentrate on pupils without SEN (55% of all observations involving the teacher), while pupils with SEN, in comparison to the other groups, had more interactions with TAs (41% of all observations involving TAs). The results clearly show that TA interactions with pupils increase, and teacher interactions decrease, with rising levels of pupil need.

Reassessing the Impact of Teaching Assistants: How Research Challenges Practice and Policy by Peter Blatchford, Anthony Russell and Rob Webster - an indispensable text for primary school teachers and senior leaders - is available now, published by Routledge.

Peter Blatchford is Professor of Psychology and Education at the Institute of Education. Rob Webster was a researcher on the DISS project and worked for six years as a TA.

If your marking doesn’t affect pupil progress - stop it!

Ace-Classroom-Support

Use the bottle-flipping craze to create good school behaviour, not bad

Behaviour Management

5 Ways To Celebrate World Book Day

Ace-Classroom-Support

Teaching Mandarin via video conference

Languages