Kevin Harcombe shows you how to seize control of the curriculum and infuse it with creativity...

Creativity in the curriculum has sometimes been confused with doing more painting and music, but it’s about the how not the what, especially as the what is somewhat prescribed. Creativity is about learning in a way that adds the wow factor and is memorable. (N.B. This does not mean writing a poem about science. “I wandered lonely as a bunsen burner” doesn’t really cut it.)

Some schools are still firmly wedded to the QCA schemes of work. They cover all the bases and are a useful starting point. But that’s all they are. So much more is possible. Having said this, when designing your bright, shiny, creative curriculum don’t throw baby out with the bathwater. Instead add bubbles, fluffy towels, some good splashing games and singing. (When Sir Jim Rose visited my school he said his first duty on his curriculum review was “do no harm”.)

There are actually are very few rules - the strategies have never been statutory. It’s up to schools to be as creative as they like whilst always remembering the importance of attainment and standards. First-hand experience should be paramount. The best way to learn about rivers is to go and see one and maybe paddle in it. Although, at primary age, this maxim does not extend to volcanoes. Just imagine the risk assessment forms!

Mick Waters, former director of curriculum at QCA, recently gave some excellent advice: don’t spend all your money on text books – take the children somewhere interesting instead. This is a great way to add creativity. Plan at least two or three days out per year and four or five local walking visits (usually the biggest cost of any trips is the coach hire). Get the children outside, even if it’s only into the playground or school grounds.

On occasions when you can’t venture beyond the classroom, the outside world can come to you. Plan at least one visitor to the class/year group/school per term. This does not have to be costly. There are lots of local people who want to reach out to schools. We had the local planning officer in to talk about how the new shopping centre was being developed. We have also forged links with our local theatre and had great visits from hearing dogs for the deaf, RSPCA ark, nurses, doctors, police, etc.

Book weeks, science weeks, etc. are fantastic occasions. You can get an author to visit for as little as £250 a day and they’re always excellent value for money.

The best way to learn about World War II – given that children can’t ‘visit it’ – is to recreate aspects of the conflict. If you can’t afford a visit to a war museum, or even if you can, get ‘walking memories’ into school – those who experienced WWII at first hand. If children frame their questions in advance, you can have a class vote over which questions will be asked.

Get artefacts to handle and to wear, make a war time recipe and eat it – children love lessons they can scoff! – and learn songs of the time. (Yes, We’ll Meet Again, by all means, but older children really like the risqué double entendres of a George Formby.)

Make an Anderson shelter – basically sugar paper framed by desks. It might not look much, but when the children creep inside as you sound your recording of an air raid siren, boy will it be atmospheric. Remember to give the all clear rather than sneaking off to the staff room for a cuppa.

Read great children’s war literature – Nina Bawden’s Carries’ War for evacuees, The Machine Gunners by Robert Westall, Anne Franks’ diary for poignancy and the human impact of the holocaust. Dig for victory! No matter if you have no space, you can plant carrots in seed trays or a grow bag in a yard.

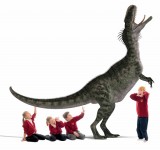

Start with non negotiable objectives and ask the children to help design the tasks – what activities will lead to success? What skills will they need to improve? What could the end result look like? Give them parameters; or pose a question and let children design tasks and use skills to answer/investigate it. For example, instead of a dull science unit about interdependence, tell them that, through DNA research, scientists are about to reintroduce the woolly mammoth, or a dinosaur – what will it need to survive in today’s world?

Use the extra curricular to support what goes on in lesson time – the curriculum is the whole of what the school offers. Notify parents well in advance – including through the VLE – so that they can lend support. If the children set up a class museum as part of a history theme, parents can visit and the pupil ‘curators’ can show them round, which hits speaking and listening too.

When you’ve planned and implemented your creative curriculum, be prepared to abandon it if there is a significant news item that is of interest and grabs children’s attention – the whale caught in the Thames could have led to work on habitats, food chains, pollution, global warming; all of which have to be covered in the national curriculum.

The point of creativity is to make stuff memorable, to shine a light on something that a drier exercise or explanation would not illuminate at all. I still recall my history teacher singing his explanation of the industrial revolution to the tune of Toreador from Carmen. It made me smile. It stopped me nodding off. It engaged me. It was memorable. How will your class remember your lessons in ten years’ time? It is not the curriculum but what teachers do with it that matters.

Use these ideas to shake up your curriculum…

Ban writing for a week

Ban writing for a week

All outcomes are recorded on video, cameras or recorders. Watch the struggling writers relax and blossom.

The new curriculum places greater emphasis on drama and speaking and listening. Hot seat Neil Armstrong, Churchill or characters in a painting. Listening to a child talking about walking on the moon will give an insight into their understanding and misconceptions about forces.

Experiment with circus science

Try plate spinning, juggling, swinging a bucket of water round your head (the centrifugal force keeps it in).

How To Use Books To Help Children Cope With Life

Ace-English

How to use Harry Potter to engage high-ability learners

Ace-Languages