To really understand the causes of extreme behaviour, teachers must step across the home/school threshold, says Paul Dix...

Some behaviours appear to be utterly irrational, some just bloodyminded. Can the search for a cause lead us into amateur social work and faux psychology or to a better understanding of the child?

Behaviour comes from a desire, a need, an urge. You may not like the symptoms but it helps to understand the cause.

The most frequent causes of the worst behaviour lie in broken trust and underachievement. The need to hide underachievement

and the shame of it is what drives the behaviour of some children. Once the child realises the colours of the table groups are linked to his corresponding ability levels, the game is up. The realisation of being left behind leaves the child gasping to catch up. Without intensive early intervention the gap becomes larger with age. It is disguised by behaviour that diverts and disrupts. If you can’t read and everyone else can it is in your interests to pretend to work/throw chairs/refuse to participate.

Behaviours that appear extreme to others are utterly rational to children who are trying to hide their embarrassment. Some behaviours are obvious and troubling: the child cries for help (in the wrong way) and it is misdiagnosed as a ‘behaviour problem’. Others lie undiscovered until secondary transfer as children cruise under the radar, failing without protest. The system punishes the chair-throwing children most severely, yet we should act with equal urgency for the children who withdraw, who silently destroy their education.

Mistrust of the adult world is accelerated by parents who split. As the foundations of family life crumble, the child knows that adults lie, often badly. The emotional trauma that warring parents can inflict on children unravels in classrooms. Anger replaces pain in short bursts of satisfaction followed by long hours of regret. The echoes of divorce ripple through lives for years and every adult who approaches you is now treated with suspicion.

Some parents damage their children and then send them in for the school to heal. I have worked in schools where children were regularly told they were not to come home and that the parent wanted to place them in care. Some parents would come at the end of the day and have this discussion with their child in front of me. You can see the damage etching itself on the child’s face. If your mother was trying to dispose of you, in public, with venom, just how important would achievement really be? You don’t need to be a psychologist to work that one out.

Unfortunately, in schools, when children need love the system gives them a label. When they are hurting and struggle to express this calmly the system cannot bend. The cliff edge for exclusion and rigidity of sanctions apply for all children regardless of individual need. We see emotional trauma playing out in schools where control, authority and sameness are central to policy and process. In curriculum we scream ‘personalise’, in behaviour we yell ‘conform!’

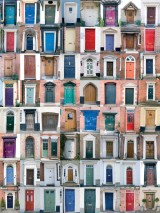

For many teachers the line between teaching and social work is at the school gates. Home visits are discouraged for many and remain the preserve of the few. But waiting for the community to come to the school doesn’t always work. You have to make the first move. I can learn so much from a cup of tea and a chat. It may not provide the solutions or satisfy urgent demands for cessation of classroom hostilities but I can begin to understand. I can differentiate my behaviour strategies and attitude accordingly. I have visited homes where everything has been sold to feed an addiction and others where the highest standards of home care are discovered behind unassuming grey doors. Every time you cross the threshold, mutual understanding and trust are increased.

For many teachers the line between teaching and social work is at the school gates. Home visits are discouraged for many and remain the preserve of the few. But waiting for the community to come to the school doesn’t always work. You have to make the first move. I can learn so much from a cup of tea and a chat. It may not provide the solutions or satisfy urgent demands for cessation of classroom hostilities but I can begin to understand. I can differentiate my behaviour strategies and attitude accordingly. I have visited homes where everything has been sold to feed an addiction and others where the highest standards of home care are discovered behind unassuming grey doors. Every time you cross the threshold, mutual understanding and trust are increased.

‘Engaging parents’ is a strange euphemism for talking to people. So many schools sit and plan ‘engagement strategies’ that rely on the parent coming to the school. Perhaps arming the willing with a packet of biscuits is the simplest, most human and most effective way to make lasting bridges.

The frustration that often exists for teachers is that they are not fully briefed when there are serious issues at home that impact on the child. They are given thin slices of information, rarely the full story. So it is with limited knowledge and improvised expertise we try to manage emotional damage and trauma, depression, anger, grief, mental health issues, abuse etc. The sword is double edged, trust teachers with all of the information and a few will misuse it, provide less detail and we risk unsympathetic interventions.

The shortening of teacher training and focus on teaching as a ‘craft’ will give teachers less time to really understand the psychology of behaviour. Their skills in managing behaviour may improve but at what cost? You can’t patch emotional trauma with great lessons and quick fix behaviour techniques - just as you can’t learn to manage extreme behaviour simply by observing others. It is not easy to dissect, reinterpret and replicate the skills/attitude/delivery of another teacher by watching them. What results from copycat teaching is practice that is diluted, moving further away from evidence/research and into ‘craft’. The toolbox may be full, but the tools are useless if nobody understands the correct way to use them.

We are not social workers but we have heart. We are not trained psychologists but we can understand. With a better understanding of the causes of poor behaviour we can deal with the symptoms with empathy, care and with the individual in mind.

Visit pivotaleducation.com for free behaviour tips from award winning trainer Paul Dix.

Do you have a behaviour issue that you would like Paul Dix to address? Or perhaps you’d like to share a comment on his article? If so, send your questions and letters to .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address) (questions will be treated as confidential).

Raise achievement by helping children to stay on task…

• How often do you give sanctions for poor conduct compared to sanctions for lack of effort? What is the balance in your classroom? Can you give greater emphasis to ‘staying on task’ in order to raise the expectation, pace and intensity of children’s endeavour?

• The problem is not the behaviour, the problem is the time pupils spend away from learning. Lower your tolerance for children who drift off task and increase the attention to the ‘stay on task’ rule. You will catch the drifters who need to be caught instead of always catching those who want to be caught.

Follow @teachprimary and @PivotalPaul to join the conversation on Twitter. Let us know your thoughts on the issues raised in the article, and put your behaviour questions to Paul.

Paul Dix is a leading voice in behaviour management in the UK and internationally. A National Training Award winner, he is a member of the Restraint Accreditation Board and has presented evidence to the Education Select Committee on behaviour.

How To Use Books To Help Children Cope With Life

Ace-English