At the Tate Liverpool, children can see how Lewis Caroll's Alice in Wonderland has influenced generations of artists says Jerome Monahan...

The little girl lies snuggled in her mother’s lap listening intently to the book being read to her. Her glance is outward at the viewer, but it is misty-eyed since the artist George Dunlop Leslie has managed brilliantly to capture the moment before her eyelids droop and sleep envelops her. Above all else the story is paramount, and a discarded doll - balancing the human figures at the opposite end of a decidedly rigid sofa – attest to its power to overcome all distractions.

George Dunlop Leslie Alice in Wonderland 1879

George Dunlop Leslie Alice in Wonderland 1879

This is one of the first images to confront the visitor to the Tate Liverpool’s eccentrically varied and fascinating exhibition focused on Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, which explores both the book’s genesis but also its rich cultural afterlife – particularly the impact it has had on the visual arts in the 146 years since its publication in 1865. At one level, Dunlop’s picture is a pretty standard bit of highly realistic Victorian sentimentality, but what makes the 1879 canvas so important is that in her blue dress and pinafore, the child is unmistakably ‘Alice’. And if this was not clue enough, the painting’s title also echoes Lewis Carroll’s book. As assistant curator Eleanor Clayton points out, what we are witnessing is proof positive of the book’s impact: “Here is prominent Royal Academician paying tribute to a children’s story just over a decade on from its first appearance.”

Dunlop’s work set a pattern for artists ever since who have found in Alice’s adventures rich sources of inspiration, with every generation finding new means of response to the book’s bizarre and sometimes menacing narrative and characters. As such, this exhibition goes to the heart of some of the key elements of KS2 art anddesign that requires children to ‘collect visual and other information’ and also ‘adapt their work in the light of others’ output’.

The exhibition has noticeably attracted some criticism with suggestions some of the later 20th Century works are only tenuouslylinked to Carroll’s book, but this is certainly not an accusation that can be levelled against the show’s opening rooms which chart the book’s inception and most immediate and direct take up among artists and Victorian and Edwardian popular culture and entertainment. It is wonderful, for example, to be able to stand within a few inches of Carroll’s original handwritten and self-illustrated version of the story, created as a Christmas gift for one of the little girls, Alice Liddell, who together with her two sisters were the original audience for the tale told off-the-cuff by Carroll to entertain them on a famous boat ride up the Orwell in July 1862. This and the crudely pasted ‘proof sheet’ that shows Carroll’s arrangement of the type to fit.

A little door about fifteen inches high 1864-1865 © RosenbachMuseum & Library, Philadelphia John Wesley

A little door about fifteen inches high 1864-1865 © RosenbachMuseum & Library, Philadelphia John Wesley

The Mouse’s Tale of chapter three so that it resembles the creature’s tail, could be the perfect stimulus for children to get busy turning their own stories into picture books.

To take this one stage further and help pupils truly learn how best to meld text and image, there are the best possible lessons to be derived from studying John Tenniel’s famous illustrations for the first published edition of the story. It was his genius to portray the Cheshire Cat in two consecutive images and in flipping the page from one to the other, the reader quickly spots how its gradual disappearance is cleverly emphasised. Similarly, the image of a gigantic Alicetrapped in the White Rabbit’s house, one realises is placed so that the confines of the printed page itself seem to be constraining her. Tenniel, we learn, was also open to artistic influences with his vision of the formidable Duchess directly being inspired by a 16th Century portrait of an ugly princess by Flemish painter Quentin Matsys.

In addition, the exhibition is a tremendous means by which younger visitors can gain insights into the inter-relationships between artists and the overlaps that can ensue. Carroll was an avid gallery-goer and also forged strong relationships with a number of important contemporary artists especially members of the pre-Raphaelite movement such as Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Edward Burne-Jones, and Sir John Everett Millais whose preoccupations with the innocence of childhood were deeply sympathetic to the author’s own outlook. The show is a reminder too of how important a pioneer Carroll was in the field of photography and how wide-ranging his output was including portraits of these same artists and views of Oxford and its surrounding countryside.

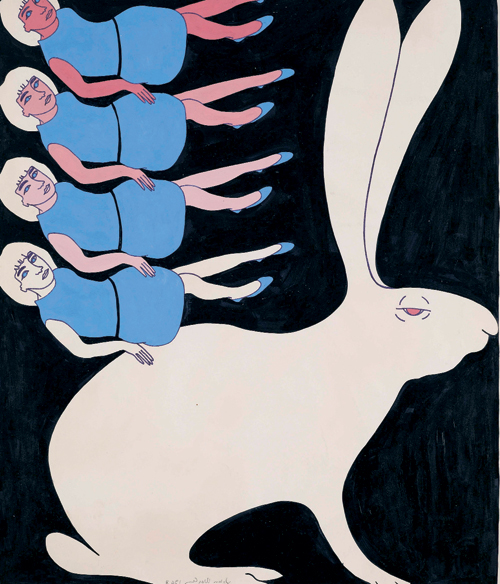

(Untitled) Falling Alice 1963 Acrylic on Paper © Fredericks & Freiser, New York Kiki Smith

(Untitled) Falling Alice 1963 Acrylic on Paper © Fredericks & Freiser, New York Kiki Smith

It will be interesting for teachers to see what their groups make of the 20th Century Alice-inspired art. The Surrealists were especially struck by the book and there is an intriguing selection of pictures on show including important works by Paul Nash, Max Ernst and Dorothea Tanning. One sculpture, that may have considerable impact is F.E. McWilliam’s 1939 Eye, Nose and Cheek which, in showing a face rendered down to a few minimal elements gains new relevance here in close proximity to Carroll’s vanishing feline. It is also a gift to a school art project inviting pupils to have a go at similarly minimalist portraits of themselves or their friends. Alice in Wonderland is at the Tate Liverpool until January 29, 2012. A number of educational resources have also been created specially for the show (tate.org.uk/liverpool).

• Invite students to attempt their own depiction of a ‘muchness’ – as inspired by the Door Mouse’s sleepy suggestion at the Mad Hatter’s Tea Party.

• Make a study of Alice through the ages including the surreal, Walt Disney and 60s psychedelic Alices on show at the Tate Liverpool. There is a similarly rich tradition of book illustration associated with the story and it is perhaps one of the show’s only disappointments that more space was not dedicated to this aspect of its artistic after life.

• Take time to explore Allen Ruppersberg’s 2007 interactive work The Never Ending Book in which you are invited to make up your own story from randomly selected paragraphs held in boxes arranged on primal-coloured plinths.

Becoming a teaching school

Ace-Heads

The side effects of teaching music

Ace-Music